‘Shrimp Boy’ Shocker

Leland Yee Corruption Case Includes Bizarre Gun and Murder Plots

In December 2012, State Senator Leland Yee called for stricter gun control laws, following the murders of 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School, speaking emotionally of the tragedy’s affect on him. “As a father, I have wept for the parents and families who lost their precious children,” the San Francisco Democrat said, “and I have felt so incredibly grateful for my own children.”

Two years later, Yee said that he could arrange the sale of $2 million worth of war grade weapons while sitting in a San Francisco coffee shop and speaking to a man whom he thought was an East Coast Mafia leader but was actually an undercover FBI agent.

His opinion of the arms sale was “agnostic,” the liberal lawmaker stated: “People want to get whatever they want to get. Do I care? No, I don’t care. People need certain things.”

The disconnect between Yee’s public and private views about guns offers a glimpse into his secret double life, as detailed in a remarkable 137-page FBI affidavit that last week led to the arrest of the 65-year-old career politician, along with two dozen others, including a longtime S.F. Chinatown gangster called Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow.

“Shocking,” “sickening,” and “surreal” were three words Senate President Darrell Steinberg (D-Sacramento) used about the astonishing scandal; while vivid, his comments fell short in describing the improbable sweep and bizarre substance of the matter.

Yee was arrested at home early on March 26, as federal agents simultaneously raided his Capitol office and nabbed the others around the Bay Area on charges of bribery, racketeering, and murder for hire, among others. A federal judge released Yee on a $500,000 bond; he will enter a plea when formally indicted.

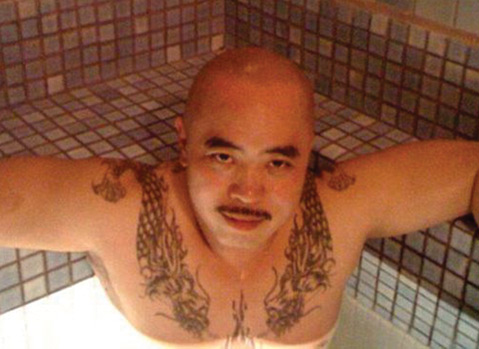

Most of the others caught up in the three-year, 14-man sting operation were not released, including “Shrimp Boy” Chow, whose gang moniker not only delighted headline writers around the state (his grandmother in Hong Kong reportedly nicknamed as a boy so spirits would protect him because of his small stature) but also recalled recent decades of violent clashes between competing Chinatown criminal organizations. Chow, who spent 22 years in prison and wears an electronic ankle monitor, has claimed in recent years that he has turned his life around and wants to help at-risk youths, earning him plaques and plaudits from Democratic politicians from S.F. Mayor Ed Lee to U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein.

Apparently, their encomiums were premature.

Yee’s predicament stems from his urgent efforts to raise campaign cash, first to pay off a $70,000 debt from an ill-fated run for mayor in 2011 and, more recently, his bid to be elected California’s Secretary of State, an effort from which he formally withdrew last week (too late for the state to remove his name from the ballot).

“Helping” him in fundraising was a controversial political consultant named Keith Jackson. It was he who broached the purported weapons deal — Yee claimed connections to armed rebels in the Philippines and gunrunners in Asia. Jackson’s son also became entangled when he urged another agent to employ him for a murder-for-hire contract.

Yee’s alleged role in the arms sale conspiracy has been heavily publicized, but it may be the least of his legal troubles; the allegation carries a maximum five-year sentence, while six corruption counts, under the federal “honest services” law, could get him 25 years in prison and a $250,000 fine each.

A day after Yee’s arrest, Steinberg led the Senate in voting overwhelmingly to “suspend” him and two other members of the house enmeshed in their own corruption cases (covered here and here). This means they will continue to get paid; many Democrats refuse to consider “expelling” the three until their legal cases are resolved.

The FBI affidavit, which has been virtually the only source of media information about the case, asserts that there is considerable wiretap and tape-recorded evidence against Yee. But some legal scholars note that corruption cases involving campaign contributions can be difficult for prosecutors; they must prove not only that a politician took money but also that in his own mind he knew and understood it was given in exchange for a specific quid pro quo rather than support for his more general views and votes.

“For prosecutors,” Steven Larson, an ex-prosecutor turned defense attorney, told the Sacramento Bee, “the singular challenge is establishing criminal intent — proving that contributions are bribes and not protected speech, something far harder to do in a court of law than the court of public opinion.”