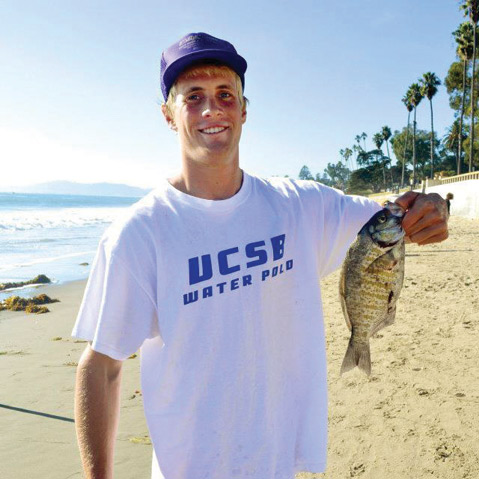

Remembering Nick Johnson

UCSB Water Polo Player Was a Bright Spirit Who Left this World Too Soon

Between paroxysms of grief, Berkeley “Augie” Johnson worries about the effect his oldest son’s death has had on anybody who might feel a burden of responsibility. “I want to stop the collateral damage,” he said. “I feel bad for the three kids who tried to save him, his coaches, his college roommates. Nick wouldn’t want anybody to feel guilty about this.”

Nicholas “Nick” Johnson, 19, a sophomore water polo player at UCSB, died on Monday, March 24, after he was found unresponsive at the bottom of the Santa Barbara High School pool during a swimming workout. Three high school swimmers pulled him out and performed CPR but were unable to revive him. A preliminary report from the Santa Barbara Coroner’s Bureau attributed the death to “accidental drowning.”

Pain and puzzlement in heavy doses wracked Nick’s parents, Augie and Dr. Karen Johnson. They had a backyard pool and made sure all four of their children learned to swim at an early age. Nick was the family’s strongest swimmer — indeed, one of the strongest swimmers in the community. He was a graduate of the Junior Lifeguard program and became an instructor of future lifeguards. To compete in water polo, as physically demanding a sport as there is, he trained religiously. It just didn’t make sense for him to be a victim of drowning.

UCSB water polo coach Wolf Wigo wants to get the message out that there is a possible explanation, a condition that can befall the most driven athletes and is so sudden and traumatic that they are beyond saving in a matter of a minute or two. It happened to Wigo 15 years ago. He was holding his breath while swimming underwater laps in a backyard pool when he blacked out. He unconsciously started to inhale water. He survived because his father, Bruce Wigo, quickly pulled him out and administered life-saving CPR. At the time, Wolf was a veteran of the 1996 U.S. Olympic water polo team, and he went on to play in the 2000 and 2004 Olympics.

Bruce Wigo, former CEO of USA Water Polo, wrote a treatise about the incident in 1999 when another highly conditioned athlete, Mexican water polo player Omar Ortega, apparently fainted underwater at the end of a practice session and died from drowning. The reason his son and Ortega lost consciousness, Wigo wrote, was a phenomenon known as “shallow-water blackout,’’ to differentiate it from blackouts that afflict deep-sea divers.

“Another term for it is ‘hyperventilation-induced hypoxia,’” Bruce Wigo said last week. Hyperventilation, rapidly inhaling and exhaling full breaths of air, is the first link in a dangerous chain of events. It depresses the level of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the lungs. The buildup of CO2 is what stimulates the brain to inform the body of an urgent need to breathe. Lacking the urge to surface and fill his lungs with air, an underwater swimmer could pass out from hypoxia, the depletion of oxygen. His lungs would be instantly flooded with water when breathing does kick in.

“Your brain gets tricked,” Wolf Wigo said. “When it happened to me, I didn’t feel the need to breathe. Sinking to the bottom of the pool, it was like I was in a dream.” He might have become a poster boy for the blackout syndrome, Wigo noted. “But I didn’t die.” Efforts to prevent drowning have been focused on making water safe for toddlers and inexperienced swimmers, not aquatic athletes.

The dormant issue sprung up again last September at the American Swimming Coaches Association World Clinic when Bob Bowman, the coach of Michael Phelps, detailed a case of shallow-water blackout at his North Baltimore Aquatic Club pool. The victim was 14-year-old Louis Lowenthal, who jumped back into the pool after a practice in October 2012. Although safety personnel were in place, Bowman said, they did not rescue him in time. He was taken away on life support and died three days later. “It didn’t make sense,” Bowman said. Lowenthal was “perfectly healthy” and “an accomplished swimmer.” It turns out that the best swimmers, Navy SEALs and elite athletes, are most at risk of shallow-water blackout because of how hard they can push themselves.

Nick Johnson was that kind of athlete. His room was full of trophies from all the sports he excelled at — BMX riding, track, road-running, basketball, volleyball, karate, rowing an ergometer, and surfing, as well as swimming and water polo. He pursued other activities that required concentration: chess and trumpet playing. His coaches, Wolf Wigo and Santa Barbara High’s Mark Walsh, said he was the hardest-working player on their water polo squads.

Johnson was practicing on his own while the high school swimmers were working out on the first day of spring break last week. Augie Johnson heard that his son was seen swimming underwater, and it now seems probable to him that Nick’s drowning was brought about by an inadvertent blackout.

If shallow-water blackout is the answer to why Nick Johnson died, there is a tougher metaphysical question: Why did Nick Johnson have to die? Why was he taken away from a family that loved him and a community that cherished him?

He was such a fine young man, cheerfully taking on the responsibility of being the big brother of his family, a role model for his younger brothers, Cooper and Sam, and his sister, Sophie. “He might have failed to take out the garbage once or twice,” Augie Johnson said. There have been numerous testimonials to Nick’s friendliness, his ability to make everybody around him feel good. He was a leader to younger athletes. He was, in his own way, saintly. And what saints do is serve as inspirations after they’re gone. Everybody who was touched by Nick’s kindness will live the rest of their lives mindful of his spirit.

It must be a family thing, because Augie Johnson is remarkable in the compassion that he feels for those affected by Nick’s death. He does not blame water polo. He is thankful for the sport that gave his son an outlet for his enthusiasm and helped get him into college. He is taking Nick’s college fund and donating some to the Santa Barbara High aquatic program and some to the UCSB program. Memorial funds have been set up at both schools.

Another after-effect of Nick’s death is bringing attention to the danger of underwater swimming. It is not incorporated into UCSB water polo workouts, Wolf Wigo said, because “there is no major benefit athletically.” But that did not stop him from trying to see how long he could last during a Christmas break 15 years ago.

“Kids are always going to test themselves by holding their breath underwater,” Bruce Wigo said. They need to know the necessity of breathing normally, rather than hyperventilating, to keep their oxygen and CO2 levels in equilibrium. Coaches, teammates, lifeguards, and monitors need to be vigilant. “I’m working on a deal to produce some warning signs to be posted at pools,” Wolf Wigo said.

“Let’s educate people if they need to be educated,” Augie Johnson said, taking what comfort he could from knowing his son did not die in vain.

4•1•1

A memorial service for Nick Johnson will be held Sunday, April 6, at 2 p.m. at the Unitarian Society of Santa Barbara, 1535 Santa Barbara Street.