1 in 5 in Poverty

Countywide Study Delivers Startling Results

The struggles of those who live in poverty reach far and wide, from what they’re able to eat and where they’re able to live, to whether they can care for their health and their kids and transport themselves to work (often multiple) minimum-wage jobs. Such is life for thousands of Santa Barbara County residents, according to a study on poverty commissioned by the Board of Supervisors in January 2012, the findings of which were presented Tuesday.

The fact that there are poor people in Santa Barbara County is not a revelation. But the study’s hard numbers and its presentation of the discrepancy between what federal standards say poverty means and what other metrics say is necessary for basic survival point to room for change in how the county’s poor are served. First District Supervisor Salud Carbajal, who proposed the study in 2011, said that for all of the study’s gloom, there is not necessarily doom. “The silver lining is that this provides us a tool to be more strategic in better serving that population in future years,” he said, explaining that he wants the statistics to help the county find ways to better align services with the people who need them and keep track of this data in the future.

The study, conducted by the Oakland-based Insight Center for Community Economic Development, focused on areas according to Census tracts and zip codes, and culled its data from the 2006-2010 American Community Survey, historical records, and primary input from more than 100 area service providers and 16 leaders of nonprofit and private organizations.

It also took into account the dueling metrics used to measure poverty. For example, the federal guidelines — the thresholds of which are based on 1950s spending patterns and don’t vary by location — classify a single person as living in poverty if they make just under $11,000 a year. For a family of three, that number increases to about $18,000. The Self-Sufficiency Standard is another metric, which is used by the majority of states and can vary by county. Santa Barbara County’s Self-Sufficiency Standard says that a single adult needs at least about $27,000 a year to pay for basic needs, while a single parent with two young children needs close to $60,000 per year — an amount not covered by even three full-time, minimum-wage jobs.

To find the county’s most-suffering pockets, the report designated high-poverty areas as those whose Census tracts exceeded 20 percent of its residents living in poverty. And after crunching the numbers, the researchers found the county’s poorest areas concentrated in Santa Maria, Santa Barbara, Lompoc, and Isla Vista.

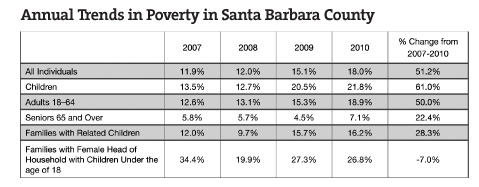

Out of the county’s 400,000-plus residents, nearly 74,000 — almost a fifth of the population — are living in poverty. Some other staggering findings include:

• In high-poverty areas, the child poverty rate is 40 percent, adults 30 percent, seniors 10 percent.

• Only about 16 percent of residents have a bachelor’s degree in high-poverty areas.

• High-poverty areas are home to 40 percent of the county’s residents using alternative transportation.

• About 34 percent of families in poverty live in South County, but they receive about half of the county’s public housing units and Section 8 vouchers.

• Nearly 72 percent of the unmet child-care needs are in the high poverty areas, with a huge portion in Santa Maria.

• In high-poverty areas, the average age of death is three years younger.

The study also found startling comparisons between how average wages for full-time jobs have changed between 2000 and 2010. While residents countywide only suffered an average yearly loss of about $21, those living in the high-poverty areas saw cuts of more than $2,000 a year. The most popular types of jobs in high-poverty areas were in agriculture, retail, and accommodation and food services — with all three sectors averaging only about $12 per hour.

Food stamp use also varied greatly between the county overall and the high-poverty areas, with about 15 percent of county households versus 32 percent of high-poverty area households using the program. The high-poverty areas in Santa Maria and Lompoc were the greatest participants.

Out of the 71,000 people countywide lacking health insurance, more than 20,000 are living in the high-poverty areas. Dr. Takashi Wada, the director and health officer for the county’s Public Health Department, said the Affordable Care Act (otherwise known as Obamacare) is projected to lower those figures over the next several years.

Although the cities of Guadalupe and Carpinteria didn’t technically meet the poverty requirements — they’re alarmingly close, though — Supervisor Carbajal said that there are “multiple levels of poverty.”

“Is one dollar really going to help you be better off than me?” he asked. “Many people are just one paycheck away from finding themselves in a circumstance where they can’t sustain their rent or put food on the table.”

Fifth District Supervisor Steve Lavagnino said that he used to live in poverty himself, but he credited a higher-paying job, not social services, with freeing him from that status. He added that he saw the study as an opportunity to work more with the area’s nonprofits, as well as increasing the number of resources in North County.

Supervisor Janet Wolf said that the results of the study shouldn’t be compared to “the perfect world,” adding, “We have situations in our county where single moms and dads raising children need some help. That’s what the county is here to do.”

On Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to keep the findings in mind for future programs and budgets.

To read the study in its entirety, visit santabarbara.legistar.com.