Squid Fishing in California

About 11 Los Angeles Coliseums-Full Caught Annually

In great numbers, California market squid (Loligo opalescens) gather to reproduce or spawn in the sandy bottoms off our coast. Birds have gathered to feed on the squid. Some seabirds can dive and swim nearly 100 feet to catch squid and other prey species.

Boats from Ventura Harbor and other destinations are also gathering to fish for the squid this time of year. At night, you may notice a network of lights flickering on the horizon on the north side of the islands and in the Santa Barbara Channel. The light-boats attract the squid and make it easier to land them in the fisher’s large purse seine or brail (or nets).

The squid on your dinner plate at a seaside restaurant has likely traveled a long road back to town. In a great irony, the squid was probably caught from the waters of our region, exported to Asia or Europe for processing and packaging, and then sent back to us for our own consumption.

There are over 285 species of fish that are landed commercially (and recreationally) along the California coast. According to the California Fisheries Atlas, commercial landings can be grouped into four main types of fished species: groundfishes, coastal pelagic fishes, highly migratory fishes, and invertebrates. There are 16-18 recognized fisheries in California for species within these four broad groupings — including about 145 species of finfish and invertebrates.

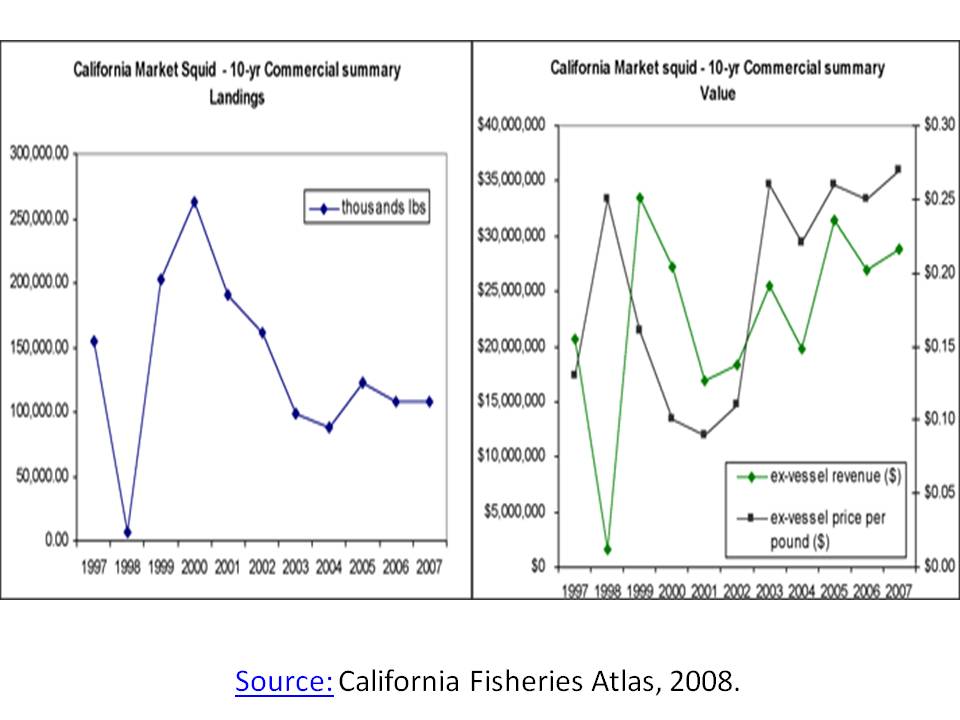

California fisheries account for about 2 percent of California’s ocean economy. Landings once amounted to more than 500,000 metric tons per year, valued at over $600 million annually. But commercial fish landings have dramatically declined since the 1980s. By 2007, they had dropped to 173,000 metric tons valued at $117 million. This decline reflects the lower volumes of high-value species, such as finfish.

The fact is that higher volumes of lower valued species, such as squid, have replaced the big fish once caught from our marine area. Today, invertebrates account for more than half the value of total commercial landings in California. Ecologists refer to this process of shifting to lower value invertebrate species as “fishing down the food chain.” Higher-value fishes have been fished out and replaced by lower-value but higher-volume commercial activities.

California’s history of commercial fishing activity is symptomatic of the loss of “big fish” across the world’s oceans. A generation ago, a recreational fisher could fill a gunny sack of rockfish from the waters of the islands. Large rockfish have all but disappeared from our waters. Arthur McEvoy describes the history of fishing in California in A Fisherman’s Problem as one that has “followed a repetitive pattern of boom and bust, one typical of fisheries the world over.”

When government determines the level of fishing pressure that should be allowed, it rarely considers the needs of other animals that depend on these species. There is a lack of ecological information on the squid stock and population. This poses a problem for the management and economic use of species.

Today, the management emphasis is primarily on what fishery economists refer to as maximum sustainable yield (MSY). Setting the MSY is a theoretical exercise based on economics and biology. The idea is that the largest yield (or catch) can be sustainably removed from the ecosystem from a species’ stock over an indefinite period of time. One goal of MSY is to maintain the population size at the point of maximum growth rate by fishing individuals that would normally be added to the population. That would thereby manage the population to continue to be productive indefinitely. The question is whether MSY is a sustainable approach to manage fishes when information on stock or population is unknown, as in the case of commercially landed squid.

Since the late 1980s, a majority of the top commercially fished species from California have been exports. Major exports. The growth of major commercial fisheries is based on the demand for these species from Asian and European markets. An excellent example is squid, which is ranked by volume as one of the state’s largest commercial fish landed. Market squid ranked sixth by volume and 16th in value among U.S. commercial fisheries’ exports in 1999 — higher than any other California commercial fish. During the past 25 years, most of the squid caught off California has occurred in the nearshore marine areas of the Channel Islands, which is one of 13 designated national marine sanctuaries.

There is no reliable scientific information on the abundance and distribution of squid. There is a lack of ecological information on the existing biomass or the status of the population of market squid. Nevertheless, the Fish Management Plan for Market Squid, developed by the California Department of Fish and Game, considers the MSY and the seasonal catch limitation to be 118,000 tons. This was coincidentally the highest landing for the fishery during 1999-2001. I asked a friend at Cal Tech to provide me with an estimate of the total volume of squid caught off our shores based on this seasonal catch limit set by Fish and Game. His rough estimate is that 118,000 tons is 11 L.A. Coliseums full of fish.

The presence and abundance of the squid in California marine areas are of paramount importance to the millions of fishes, birds, and mammals that compete for this resource with human beings. The market squid is a principal forage item for a minimum of 19 species of fishes, 13 species of birds, and six species of mammals.

The presence of local commercial fishers is one distinctive feature of our region. Their local maritime knowledge is unique and needs to be preserved with the fish they catch. While our harbor includes some of the last remaining commercial fishing boats along the South Coast, we should still question the scale or level of fishing when we decide to eat a wild-caught fish. The level and amount of fish removed from marine ecosystems of our region matters.

If we are to support a slow-food movement for the marine environment, we need to think about how we economically use the fish protein from our marine systems and the ecological importance of the fished species. Like squid, most of the other top commercial species, notably sea urchin, among others, are exported. Consumers in other regions might or might not consider it, but we certainly need to recognize the importance of many of these species to the marine life off our coast. Birds, seals, whales, and a range of other organisms depend for their survival on the return of the squid.

Overall, “globalized” industrial-scale fishing activities may not sustain the essential ecosystem services that we all depend on. We should think about where our seafood comes from, how it was caught, and the ecological costs of industrial-scale fishing. Walk the dock on Saturday morning. Buy the white sea bass or halibut or other locally caught fish from the fisher. If squid is available, ask the fisher how to prepare it for your family. Engage the fisher in a conversation. Consider the role the fish plays in the ecosystem, the type of fishing gear used to catch the fish, and where the fish is sold.

Fishers can contribute in many ways to our economy. But it can also be an extractive industry that threatens the health and integrity of marine ecosystems. Encourage local fishing, but also don’t hesitate in challenging the resource use of the maritime commons. Each of us is dependent on a healthy commons — it is our common heritage.