Rental Mediation Program Under Budget Axe

Cutback Critics Call Potential Move 'Unnecessary, Severe, and Harsh'

Compared to the massive cuts many government agencies are now confronting, the $55,000 shave-and-a-haircut proposed for Santa Barbara’s Rental Housing Mediation Task Force might appear to be little more than a scratch. But numbers tell only part of the story. That relatively modest loss of funding would effectively gut what for the past 35 years has been one of City Hall’s quiet success stories — a neutral ground where landlords and tenants (predominantly low- and very-low-income) can effectively negotiate their differences outside the costly and time-consuming confines of the court system.

If the cuts go through as proposed, the mediation task force will, in fact, cease providing any mediation services at all. Currently, that function is provided by 15 volunteer mediators, all appointed by the City Council, who are paid nothing. Two part-time employees who provide the mediators’ administrative support — as contract labor rather than salaried staff — would lose their jobs. The task force would be reduced to a glorified information hotline where landlords and tenants, in legal distress about their respective rights and responsibilities, could call. Office visits would no longer be allowed.

Last year, the task force mediated 42 cases and handled 1,200 staff consultations. The year before that, it mediated 64 cases and fielded 1,400 consultations. Most calls come from tenants concerned about security deposits, evictions, or terminations of tenancy. Many involve disputes among tenants themselves. About 20 percent of the calls come from landlords. Again, numbers can be deceiving.

One mediation can involve a lot of people, as was the case in November 2008 when the task force was called in to handle what could easily have escalated into a high-profile meltdown involving 206 tenants at the Hillshore Gardens apartment complex on Modoc Road, 90 of whom were kids.

A new owner — MRP Santa Barbara — had just bought the complex and wanted to fix it up and charge higher rents. To get the work done, the existing tenants — almost all low-income, Hispanic, and Spanish-speaking — would have to go. They were notified in October that they’d have to be out by December 12, coincidentally, the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe. For parents with kids in school, the landlord’s letter meant finding new digs and probably a new school in a hurry. Competition was fierce. In the wake of the still-smoldering Tea Fire, the demand for rentals was intense. Making matters worse, tenants were given little reason to believe they’d see their security deposits.

In initial press accounts, the landlord rejected mediation as an option. But PUEBLO, a politically influential grassroots organization, threatened to raise hell. Officials with the mediation task force asked MRP to reconsider; it did. After meeting around a very large table for nearly five hours, the parties came to an understanding. The tenants would still have to go, but they were given 90 days instead of 60. And they got their security deposits refunded. The landlord also pledged to help them find new quarters in other properties owned by MRP. And the additional time allowed Santa Barbara’s ad hoc machine of social-service organizations to kick into overdrive to help tenants during the impending Christmas season.

“It was a positive experience,” said Kevin Hansen, an agent for MRP, of the mediation process. All the tenants vacated the premises by the agreed-upon date, and Hansen said he routinely recommends the task force for tenants, especially those embroiled in roommate conflicts.

Santa Barbara Mayor Helene Schneider termed the task force’s contribution as “Huge, really huge.” Councilmember Grant House added, “It will be a real tragedy if it goes away.” But they are just two out of seven votes on a City Council confronting a $2.7-million budget shortfall. The task force’s lifeblood over the years has been federal dollars, funneled through the Community Development Block Grant program. But those federal dollars have been drying up; last year they dropped to the tune of 16.5 percent. In addition, the mediation task force will have to assume a larger amount of administrative costs than ever before. A clever bureaucratic scheme of robbing Peter to pay Paul had underwritten some of the task force’s administrative costs in years past. But this year, “Peter” — a Housing Rehabilitation Loan program run by City Hall — has since gone out of business, leaving the task force to make up the difference.

Making matters dicier still, it remains uncertain whether the County of Santa Barbara and the City of Carpinteria, which have traditionally kicked in $33,000 combined to keep the task force operating, will be good for the money. Barring a sizable infusion of private grant funding — which has been applied for — the only way to keep the task force whole is an infusion of money out of the city’s General Fund. If that were to occur, it would be the first time the task force has ever received General Fund dollars. Competition for General Fund dollars is intense. Not only is there a budget shortfall, but it’s an election year, and the council is under mounting pressure to increase funding for additional cops to keep a lid on gangs and transients. With conservatives enjoying a 4-3 majority on the council, task force supporters face an uphill fight.

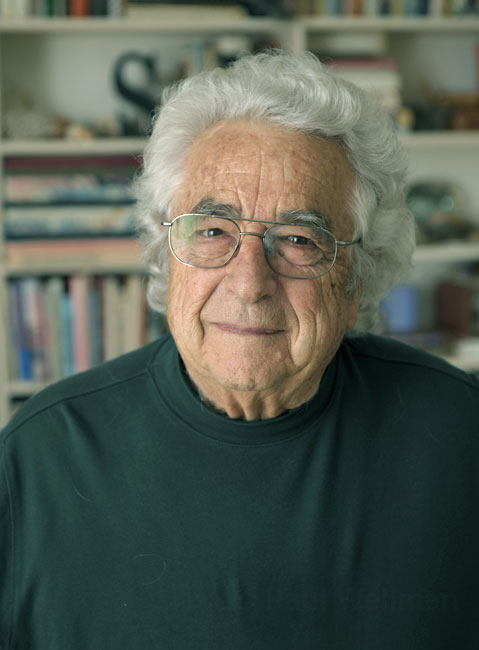

Leading the charge on behalf of the task force is classic old-school civic booster, realtor, and self-described conservative Silvio Di Loreto, who has served on the task force since its inception in 1976. In a recent letter to Brian Bosse, Housing and Revelopment manager for City Hall, Di Loreto termed the budget proposal as “an unnecessary, severe, and harsh remedy,” reminding Bosse that many of the tenants who rely upon the task force’s mediation services are among the most vulnerable and fragile in the community. He noted that the task force was created at a time when landlords and tenants had nowhere to resolve the disputes outside the legal system. That frustration, he said, gave rise to political polarization within the community.

Rather than cut the mediation function from the task force, Di Loreto urged Bosse to pursue independent fund-raising efforts. Bosse, in fact, submitted a $60,000 grant with the Santa Barbara Foundation. And if that fails, Di Loreto said, mediators should be placed on standby status in case of wholesale evictions or other emergencies. To eliminate the mediation board, he warned, would give Santa Barbara’s body politic a serious case of indigestion. “The elimination of the board would seriously overburden the duties of the elected officials,” he predicted, “who would be inundated with calls from dissatisfied constituents begging for some form of relief.”