In Deep Water

UCSB Professor’s Book on Gulf Oil Spill Released by MIT Press

In his just-released book, Blowout in the Gulf: The BP Oil Spill Disaster and the Future of Energy in America — co-authored with Robert Gramling of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette — William R. Freudenburg, Dehlsen Professor of Environment and Society at UCSB, notes that BP’s ill-fated drilling project was named Macondo after the setting of Nobel Prize-winning Colombian author Gabriel Garcia Márquez’s novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude.

In the novel, Macondo, blessed by an abundant natural setting, is cut off from the rest of civilization and after generations of unhealthy intimacy its citizens are swept off the face of the Earth in a cloud of dust along with the any traces of the town. Freudenburg and Gramling note that the thematic similarity between Márquez’s story and the story of offshore oil drilling in the Gulf are too rich to ignore.

Isolated by a virtually self-regulated industry enabled by federal policy and a petroleum-hungry populace, Freudenburg and Gramling argue, the decision makers at BP failed to make an honest assessment of the risks involved with drilling more than three miles below the earth’s surface. They continually cut corners to save time and money, pleasing shareholders but putting an entire ecosystem at risk, not to mention an economy dependent on that ecosystem and the lives of the 11 workers who died in the explosion. BP’s Macondo came to a cataclysmic destruction just like Márquez’s fictional Macondo.

That might seem like a serendipitous coincidence for an author. But one must consider the possibility that Bill Freudenburg’s life is filled with such coincidences. Take for instance his former teaching appointment at the University of Wisconsin. Freudenburg, who is a sociologist by training, thought it was his dream job, the one he would keep until he retired. By many accounts, Wisconsin is home to the best sociology department in the country and the university boasts a rich tradition of scholarship on environmental issues. To top it off, Wisconsin is located in the city of Madison and Freudenburg grew up in Madison, Nebraska. The stars seemed to have aligned.

Then about nine years ago, he got a call from UCSB informing him that he had been nominated for an endowed professorship. He came for a visit, thinking that he would take advantage of a free trip to Southern California in the middle of a Midwestern winter before settling back in at Wisconsin. But UCSB’s pitch turned out to be persuasive. Freudenburg was enticed by having access to an endowment. “Before, I would have to beg just to get enough funds for a bus to take my students on a field trip,” says Freudenburg. He was also intrigued by the interdisciplinary collaboration enabled by UCSB’s Environmental Studies department. All of a sudden, he had a real decision to make. His wife, Sarah Stewart, a middle school teacher, had just been advising her students not to get too comfortable and to be open to new opportunities. She should take her own advice, she thought. So Freudenburg and Stewart, deciding they were in a rut, packed up with their one-year old son, Max, and headed for the California coast.

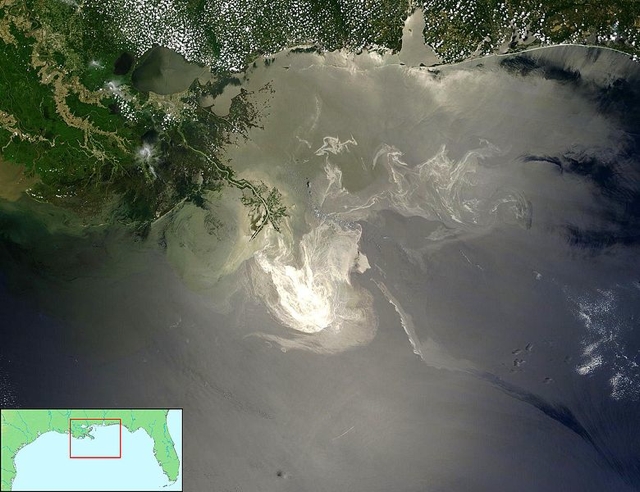

It is evident in Freudenburg’s new book, Blowout in the Gulf, that, although his life may just happen to be filled with meaningful coincidences, it is even more likely that he has an uncanny nose for sniffing them out. He points out for instance, that the Deepwater Horizon oil platform sank on April 22, 2010, the 50th anniversary of the first Earth Day celebration which was prompted in large part by the publicity surrounding the blowout of Union Oil Platform A off the Santa Barbara coast. (He is also quick to mention that his book was released exactly half a year after Deepwater Horizon fell into the sea.)

The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 also marked an important 50-year anniversary. In 1953, the U.S. Congress laid out the legal framework for offshore drilling. That year also marked the end of U.S. dominance in oil production. One goal of Freudenburg and Gramling’s book is to tell the story of how we got to the point where we are now searching for oil in the most remote and dangerous locales of the planet. (In short, we’ve used up most of the easy-to-reach oil.)

As Gramling puts it, “The main question the book asks and answers is: How in the world did we find ourselves in a situation where we are drilling in such deep water and calling it normal? Is there anything we can do about it?”

Freudenburg’s penchant for seeking out the connections between seemingly disparate events serves the greater purpose of telling stories. Blowout in the Gulf is a perfect example. It is less an academic tome than a collection of stories. The preface opens with a tale of the first witnesses to the Deepwater Horizon blowout, a group of area fisherman who were catching bait near the platform. Although Freudenburg and Gramling are academics, they keep jargon to a minimum, and arrange their data via narrative. That is, they subjugate facts and figures — of which there are plenty — to the stories they tell, which in turn makes their book eminently readable even to the nonspecialist.

Storytelling itself is central to human existence. For what is life itself but a collection of random experiences until we link them together with the connective tissue of narrative? Until we say, first this happened, then that happened. This is what they had to do with each other. Here is why it’s meaningful.

Freudenburg, already deft at this activity, has reason to engage in it even more so now. He is currently undergoing treatment for bile duct cancer. He has already outlived the original one-year prognosis of his doctors, but he knows his time is limited. In a sense, Blowout in the Gulf is a culminating work for him. He and Gramling wrote it in only 60 days and MIT Press rushed it to press in order to beat out the gusher of books on the oil spill that are certain to hit the market soon.

Freudenburg says that another way to look at the book’s speedy release is that it took 60 years to write. He and Gramling have each spent more than 30 years studying the oil industry. They have collaborated on three books and more than 20 journal articles. As a sociologist, Freudenburg specializes in studying both risk assessment and organizations that are made up, he says, of “humans, hardware and habitat.”

A central feature of Deepwater Horizon’s demise was an organizational risk that sociologists call an “atrophy of vigilance.” When an organization avoids catastrophic failures for a long enough period of time, it cultivates a false sense of confidence and starts to get lax about enforcing the very precautions that prevented disasters in the first place. BP was a case study in such behavior.

Along with the owner of the platform, Transocean, and the contractor, Halliburton, BP cut several corners — which are detailed in the book — in the construction of the drilling well that failed. BP’s drilling engineer called it a “nightmare well.” Furthermore, the last defense against an unchecked geyser is a device called a “blowout preventer,” which includes an apparatus like an axe that slices through a leaking pipe and cuts it off. Blowout preventers are fairly reliable, but it is common knowledge that they are not 100 percent. Freudenburg likens a dependence on blowout preventers to playing Russian roulette. You can load one chamber of a revolver, point the gun at your head, pull the trigger and the odds are you’ll keep your brain intact. “But,” Freudenburg says, “most people would say that isn’t a very smart thing to do.”

If BP is guilty of perpetrating organizational atrophy of vigilance, though, so is the American public. We keep investing in an unsustainable and polluting energy source and get little in return. “Energy independence has not been possible since Elvis was singing,” says Freudenburg. The United States was once the major supplier of petroleum to the world, but those days are long gone. We import the majority of our oil, a majority that keeps growing. And we let oil drilling companies get away with tax rates that are about one third of those paid by the average non-energy business. Through royalties, leases and taxes, the citizens of the United States make about 40 cents on every dollar profit companies reap extracting our oil. This is half or nearly half the take of oil-producing countries such as Norway (75 percent), Kazakhstan (80 percent), and Vietnam (80 percent).

Part of this has to do with the vast amount of wealth the industry invests in lobbying, $340 million between 2008 and 2010 alone. The returns on this investment — calculated by Gramling and Freudenburg to add up to $30 billion in tax giveaways over the 10 years — easily make it worthwhile. Alternative energy companies have nowhere close to the wealth necessary to lobby on such a scale. So we keep on investing in oil exploration even as there is less and less oil to discover.

Freudenburg’s stories add up to a moral lesson. In one sense, Blowout in the Gulf is a big “I told you so” to the oil industry. “Just about nobody in the [oil] industry has taken our advice in the past,” Freudenburg says. On the other hand, it is a wake-up call to readers. We are allowing for policies that he says “encourage burning a precious resource faster” without investing in alternatives.

In communicating a message of conservation, Freudenburg follows in the intellectual tradition of one of the great conservationists associated with his former institution, the University of Wisconsin. Aldo Leopold, Wisconsin’s first professor of game management, wrote an essay called “Thinking Like a Mountain” about a conversion experience that led him to his position on preserving ecosystems. While hunting on a mountain in Arizona, he wantonly shoots a female wolf whom he thinks of as a competitor for deer. He is immediately regretful, however, as he watches “a fierce green fire dying in [the wolf’s] eyes.”

On a practical level, Leopold learns that endangering wolves leads to an overabundance of deer and the defoliation of mountains. On a deeper level, by looking through the wolf’s eyes, Leopold is able to look at himself from the perspective of nonhuman nature, trading in egocentrism for what some environmentalists call “ecocentrism,” a sense of noncentered connectedness with other organisms and even inanimate entities. Leopold learns to see himself as a being whose relationships span across species and past his own immediate, human desires. Even in the act of dying, the wolf teaches a lesson to the man who threatens her habitat.

Freudenburg and Gramling aim for a similar message in Blowout in the Gulf. Near the conclusion, they return to the comparison of the two Macondos and quote Márquez, who writes that “races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth.” Worse than death itself is the solitude that results when we stop looking outward and sharing the stories that sustain us as a community, even as the fire is dying in our eyes.

4•1•1

UCSB’s Environmental Studies Program will be hosting a free and public lecture by Dr. Freudenburg on his book Monday, November 15, at 5 p.m., on the UCSB campus in Broida 1610.