The Undefinable Genre

An Excursion into KCSB's Varied Jazz Library

When it comes to jazz, people have their opinions. It won’t come as a surprise to KCSB listeners that the hosts of the jazz shows throughout its history have had even stronger ones. A flip through program schedules of the past reveals that most shows falling under the “jazz” category have operated under fairly particular, even idiosyncratic definitions of the genre.

Some jazz-minded KCSBers seem to have believed that real jazz existed only before a certain year; others that it existed only after a certain year; others still that it existed only within a vanishingly narrow era between one year and another. Some have thought that it isn’t real jazz unless it’s as melodic as possible; some have thought that it isn’t real jazz unless it’s as amelodic as possible. Some have claimed that real jazz is, in fact, spelled “jass.” These conflicts roil on today, their solutions nowhere in sight.

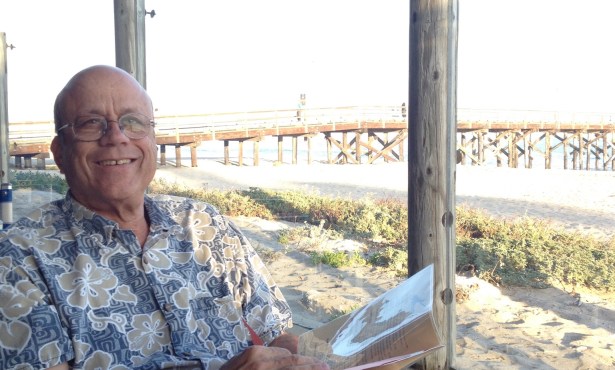

Take a look at the relevant wall of KCSB’s music library, and you’ll find the raw materials of any sub-sub-variety of jazz show that’s been done on the station and an infinitude of possible jazz shows of the future besides. Pulling out a few vinyl albums, holding them up beside one another and wondering what they could possibly have in common, I knew my next column on the station’s music library had to be an examination of its jazz collection. Back in April, when I sought out an international range of records, we saw reason to suspect that one could craft at least a respectable quarter’s worth of programs on Japanese jazz, if one were so inclined.

My way back in was finding even more of the stuff. I happened upon a cache of material from Sadao Watanabe, the prolific Japanese baritone saxophonist whose long-standing popularity on both sides of the Pacific ensures that his charmingly goofy album covers pop up in most any record crate, shelf, or bin through which might dig. Orange Express, from 1981, has the player, clad in his then-trademark white suit, standing alone alongside a desolate desert highway. As always, he’s nonetheless all smiles. The very same brand of cheerfulness pervades his music, which back then tended toward the tropical. While easy to like and even easier to put on in the background of whatever you happen to be doing, this is clearly the sort of thing that would be denounced by any self-proclaimed jazz purist. They would call it “pop jazz,” no doubt, and would quite possibly shake you down for your lunch money were they to catch you playing it. But I would argue that even the poppiest jazz albums contain a few artistic moments; properly curated by a brave deejay, they’d make a fascinating program.

Elsewhere in the racks, you can find much from ECM, a label that is many things, though poppy is most certainly not one. Its name stands for “Edition of Contemporary Music,” with all the sonic and compositional boundary-pushing that implies. Allow me to confess right now that I am a hopeless ECM addict. The always-intriguing nature of the musical selections themselves and the immaculate quality with which they’re recorded, team up, effortlessly persuading me to part with whatever cash it takes to snag their latest release or a recently unearthed rarity.

And at the risk of projecting utter superficiality, I simply can’t get enough of their cover designs. ECM is, and has been since its inception, the world leader in mesmerizingly artistic sleeves. These images blur the boundary between natural-world photography and abstraction, somehow representing the musical contents with perfect accuracy.

It was thus with some surprise—though not too much, since KCSB is a place of surprises—that I discovered in the music library an ECM title I’d never heard before. Codona 2 is a 1980 release (logically enough, the second one) from the group Codona, whose recordings are pitched somewhere between Ornette Coleman-style free jazz and what we would now call “world music.” This hybridity makes sense when you consider the trio’s background: cornetist Don Cherry began his career in Coleman’s band, sitarist Collin Walcott studied with Ravi Shankar, and percussionist Naná Vasconcelos has been a go-to guy for the Brazilian vibe for decades. Though this album might reach too far outside of jazz’s American traditions to win the favor of the music’s hardcore devotees, its improvisational spirit could still earn their grudging respect. Giving it a listen reminds me that, while KCSB has a few world-music shows, it still lacks something I consider critically important: an all-ECM hour. Or three.

But while I consider ECM’s covers to be paragons of taste, it must be said that paragons of anti-taste catch my eye just as easily. This brings us to Alex Cima and On-Line’s Solid State, an album apparently set in a world where statuesque female archers pose nobly in front of starfighter-encircled sunbursts, taking aim at enormous space stations from their lush, pastoral vantage point. Oh dear. Being from 1986, it’s also infused with that techno-optimistic time’s willy-nilly embrace of computer terminology. Even beyond the band’s name and the record’s title, we’re offered tracks called “SM6,” “Control,” and, simply, “High Technology.”

This was a day when synthesizers, sequencers, and electronics of every variety flooded the ultra-mainstream world of pop, rock, and pop-rock. But unless you were listening closely then (or are spending an inordinate amount of time in a freeform radio station’s music libraries now) you might not know that the influence of late-’80s synthesized hits then proceeded to bleed back into other genres as well. Not even recordings such as those on Solid State, which would ultimately come to be categorized as jazz, were safe from Top-40 drum patterns, soaring electric guitar solos, “high-energy” vocals, and keyboard riffs we’d now associate with A Flock of Seagulls. But what’s particularly interesting here is that these cuts are interwoven with equally synthesized but much more improvised pieces that, despite their surface sheen, do indeed seem to be jazz. Encouraging news, surely, for any deejay planning a show that unites these estranged musical traditions.

“There have been over the years occasional attempts to marry Bach and jazz,” insist the liner notes to the Pierre Gossez Jazz Quintet’s 1969 attempt to do just that, Bach Takes a Trip. This, it seems, represents one of the outer limits of the KCSB jazz library, where it mingles with classical. (See also this column’s foray into the classical section itself.) Given sufficient research and preparatory listening, most any deejay could probably figure out how to assemble a decent few hours of Japanese jazz, synthesizer pop jazz, free jazz, or sitar-based jazz programming. But I would submit that, when that’s accomplished, the ultimate challenge of uniting jazz and classical on the airwaves still awaits. I’ve pointed you toward a place to start with Gossez’s outing, but beyond that, I’m afraid you’re on your own.

Interested in exploiting KCSB’s jazz library by starting a show of your own? Keep an eye on KCSB.org for summer orientation dates. Please direct any feedback to colin@independent.com.