Last-Minute Onslaught of Mud

Political Campaigns Getting Down and Dirty

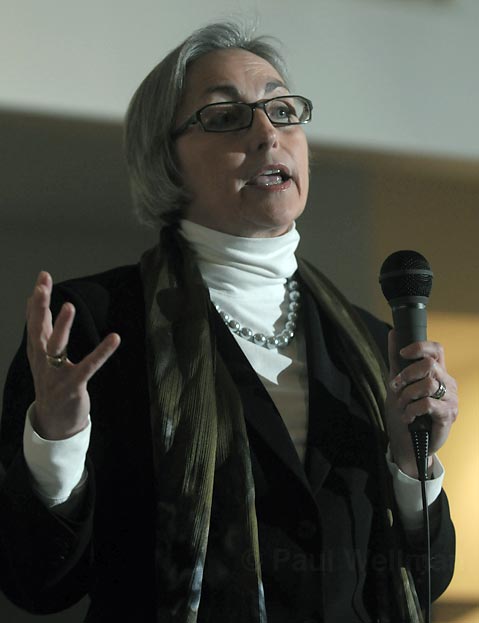

With the June primary election just days away — next Tuesday — voters can expect a blitzkrieg of campaign mud smearing their TV screens and in their mailboxes over the weekend and early next week. The Democrat primary for the 35th Assembly District has generated the most contentious and over-the-top aspersions thus far, prompting the head of the Santa Barbara Democratic Central Committee to take both candidates — Santa Barbara City Councilmember Das Williams and coastal advocate Susan Jordan — to task for engaging in “cheap shots and character bashing.”

Late this week, Williams escalated the simmering war of words by sending out a flyer accusing Jordan of being a “guest of the Schwarzenegger Administration on a luxury junket” sponsored by oil and energy companies. The mailer shows a photograph of an elegantly dressed Susan Jordan that had been altered, via the magic of computer graphics, to show her holding a champagne flute in her right hand. (The photo was taken at a campaign fundraising event where Jordan said she had nothing to drink. Williams’s campaign team acknowledged the photo had been doctored for dramatic effect.) Another photo depicted a make-believe hotel hallway with Susan Jordan’s name affixed to two doors. Next to hers were doors bearing the nameplate “Oil companies” and logos from Shell Oil and Chevron-Texaco. The ad suggests that Susan Jordan joined oil and energy executives as a guest of the Schwarzenegger administration on a luxury, five-star trip to Asia and Australia — paid for by the oil and energy companies. The clear impression the ad conveyed was that Jordan had taken up to $8,000 in travel expenses from oil companies on a luxury travel excursion — including nights at the Four Seasons and a yacht cruise — and that she was politically cozy to an inappropriate degree with Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican.

Williams said his ad was designed to retaliate against Jordan’s charge that he supports oil development, that he’s been backed by the oil industry, and that he’s been funded by oil companies. Both Williams and Jordan have strong environmental credentials; both have strong anti-oil records they can point to. But they differ sharply over one very significant and controversial offshore oil proposal — PXP’s, off the coast of Lompoc — and both have sought to tar the other with the oil brush. Given Santa Barbara’s major oil spill in 1969 — which helped give birth to the modern environmental movement — the issue is charged. But given the cataclysmic oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, it is especially so.

The PXP proposal — which is now dead after having been voted down at the state level numerous times — has generated intense controversy. Williams continues to voice support for the proposal because of its support from key leaders of the South Coast environmental establishment. In exchange for their support, PXP had agreed to shut down oil production at an existing oil platform sooner than it would otherwise. In addition, PXP agreed to remove much of the onshore industrial infrastructure upon which any coastal oil development would rely. Jordan parted company with many of her allies in the environmental movement and has vigorously fought the proposal, arguing it’s legally unenforceable, that it sets a dangerous precedent, and that it could open up the entire coast of California to new oil drilling.

While Williams’s mailer was accurate in certain details, it was inaccurate in others and misleading overall. The trip was paid for by the California Foundation on the Environment and the Economy, a nonprofit foundation and think tank that’s funded by the fees it charges its membership. While many members do come from the oil, gas, and energy industry, others come from other labor unions, other business sectors, academia, government, and some environmentalists. While the Foundation is tilted heavily toward business interests, the vice-chair of its board is a member of the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). Jordan, in fact, participated in the trip — an 11-day inspection of liquefied natural gas plants in South Korea and Australia — at the invitation of the NRDC, whose representative for the trip could not make it. Jordan at that time was actively engaged in a campaign to block a proposed LNG plant off the coast of Ventura. Gov. Schwarzenegger was not present on the trip, but three members of his administration were. While the Foundation stresses that it represents a broad section of energy stakeholders — not just the industry line — Jordan herself acknowledged that she was the sole LNG critic included, and that it was her perception that most of her colleagues on the journey would have preferred she not be there.

To an unusual degree the Democratic primary has all the hallmarks of a nasty family feud. Williams and Jordan are former colleagues, comrades-in-arms, and even friends. So too are many of the activists lining up on opposing sides. In this context, it’s hard to tell where the political differences end and where the personal ones begin.

Williams has objected that Jordan has portrayed him falsely and unfairly as the pro-oil candidate. She has sent out numerous mailers showing British Petroleum’s burning oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico juxtaposed with photographs of Williams and Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. Aside from his support for PXP, Williams has a long history of opposing offshore oil and as an environmental advocate. Jordan contends that she’s hewing strictly to the facts, and that most of her broadsides against Williams are limited to his support for PXP, not oil in general. While that’s mostly true, it’s not entirely accurate. In one email sent out to media outlets, Jordan charged that the “special interests” were lining up behind Williams and included among them were oil and energy interests. She has also stated he’s taken money — $5,000 from Texas oilman T. Boone Pickens. She noted that an oil transport company in Northern California donated $500 to a Williams’s mailer — proclaiming his opposition to offshore oil — that was paid for by an independent expenditure committee associated with tribal gaming interests. Williams objected, saying the check had been returned.

Williams has also charged that Jordan campaign workers have telephoned prospective voters and said that Williams is taking big bucks from big oil. Jordan has vehemently denied this, insisting that her telephone scripts don’t even mention Williams. But Beverly Grant, a Carpinteria School Board member and strong supporter of Das Williams, claims she was contacted by a woman claiming to represent the Jordan campaign and stating that Williams was in fact was receiving large sums from oil companies and their proxies.

Williams acknowledged he’s taken considerable criticism for his anti-Jordan mailer, but said he was bracing for the weekend onslaught of hit-pieces from independent expenditure committees supporting Jordan. Campaign records indicate that one such group, No Louisiana in Santa Barbara, had purchased $35,000 worth of TV ads. By law, there can be no coordination between independent expenditure campaigns and the candidates on whose behalf they work. But Williams’s campaign officicials noted that Assemblymember Pedro Nava — Jordan’s husband — donated $5,000 to that committee, only to withdraw it shortly thereafter. It beggared credibility, they charged, to believe that Jordan and Nava — as spouses — would not discuss such matters. Jordan’s campaign dismissed such suggestions as “ludicrous.”

One of the donors to No Louisiana in Santa Barbara is Steven Blank, a Schwarzenegger-appointee to the California Coastal Commission, a dot-com multi-millionaire out of Menlo Park, and an activist with the Audubon Society. Blank also gave $25,000 to the campaign of Dan Secord, a moderate Republican hoping to unseat incumbent 2nd District Supervisor Janet Wolf. Wolf has sought to argue that Secord has been bankrolled by North County agriculture and development interests hoping to re-take a board majority — with Wolf, the slow-growthers enjoy a 3-2 advantage — so that they could redraw the supervisorial districts to ensure their continued domination. Secord has sought to portray Wolf as a patsy of public employee unions, which have donated substantial sums — one union gave $60,000 — to her campaign. Secord is also seeking to make political hay from the PXP vote, challenging Wolf to renounce her support of the project in light of the Gulf oil spill. Secord claimed that he voted against PXP as a member of the Coastal Commission in 2005. He claimed that Wolf voted in favor of PXP when its environmental impact report was appealed to the county supervisors.

In this case, Secord’s campaign rhetoric overstates the facts. While he did vote against PXP in 2005, the vote had nothing to do with the proposed project that’s generated so much controversy. Rather it had to do with a number of offshore leases in federal waters controlled by numerous oil companies — including PXP — that had not been developed for many years. The Coastal Commission was asked to ratify a resolution opposing an extension of the leases, arguing that the oil companies had already been given ample time to develop them. If they failed to act in a timely fashion, the resolution contended, the leases should be allowed to expire. Environmentalists contend that Secord voted against extending these leases, but only reluctantly. Likewise, Wolf’s position on PXP is a bit more nuanced. She did vote to reject the appeal of the environmental impact report and to approve the project, but at that time, the State Lands Commission had not yet opined that the deal struck between PXP and the environmental community was legally unenforceable. To date, State Lands has now issued two reports to this effect. Unlike Williams, who has affirmed his support for the PXP deal, Wolf has said her support was conditioned upon it being legally enforceable.

But given Santa Barbara’s political history, the rhetoric of oil development is written in big fat letters, not fine print. Given the large number of undecided voters in both the 2nd District race and the 35th Assembly battle, it’s little wonder that oil has emerged as such a hot-button issue.