Less Aid for AIDS

Cuts to Pacific Pride Foundation Hurts HIV/AIDS Patients and Threatens the Future

A woman discovers she is pregnant. Upon going to the doctor, she makes a second discovery: She is also HIV positive. Many who hear about this situation-which, tragically, is not a hypothetical one in Santa Barbara County-would assume that the unborn child now has a death sentence. But this need not be the case. With proper medical supervision, the child can remain HIV negative. The prevention of mother-to-fetus HIV infection may seem miraculous, but it actually results from strict adherence to a regime of immunity-boosting and antiviral medication.

Ramiro Diaz knows the routine well. In the last year and a half, he and other employees of Pacific Pride Foundation (PPF) have helped six North County mothers save their babies from infection by teaching the women how to take their medication properly, by making appointments with their doctors and driving them there, by constantly checking in on their progress, and, perhaps most importantly, by earning these women’s trust.

The most recent pregnant, HIV-positive woman to utilize PPF’s services would seem to be a success story. In August, she gave birth to a child who, according to preliminary tests, also appears to be healthy. (Children whose mothers are HIV positive during their pregnancies must be tested periodically until they’re 18 months old before doctors can be sure that they do not have the disease.) Diaz, however, can only wish her well at this point, as he is one of the 11 PPF staffers laid off in the wake of a July 28 line-item veto by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger that eliminated $52 million in state funding for HIV/AIDS prevention, outreach, and testing. The action-preceded by previous cuts-eliminated $600,000, 52 percent of PPF’s funding, leaving former and remaining staffers alike to wonder how the organization would be able to muster the personnel to extend the same level of help to current and future clients.

In light of the cuts, some PPFers suggested that the next child born to an infected mother could potentially end up sharing her terminal illness. However, that possibility-which is already smallif preventative medical measures are taken-must be considered alongside the fact that no documented mother-to-child transmissions have occurred in the county during the past 10 years, thanks largely to HIV tests being a compulsory part of prenatal programs, including those offered by the county’s Public Health Department. Despite that safeguard, PPF employees working on the frontlines of the fight against this disease worry that every reduction in service means one more crack through which patients could fall.

At stake in Santa Barbara County is the fate of PPF’s 590 clients, a more diverse group than some might expect. According to the organization’s records of clients from the past fiscal year, 266 of them hail from South County, 324 from North County. Men number 395, women 195. About 55 percent are Latino, and 95 percent are considered extremely low-income, which is $14,100 or less for a one-person household, $20,150 or less for a four-person home. And 153 clients are younger than 18 years old, though this number includes infected youth as well as healthy dependents of infected adults. (For comparison’s sake, the most recent statistics from Public Health report that 461 county residents are living with HIV/AIDS, though an estimated 25 percent of people infected with the disease are unaware of it, so the actual number is higher. Of those documented as being infected, 86 percent are male, 72 percent live in South County, and 65 percent are 40-60 years old.)

Despite their disparate backgrounds, PPF clients all depend on the organization to get help just to survive-from food pantry necessities to help with prescription snafus-but also for a sense of community, and a chance to talk to people who understand their disease and its complications. PPF’s other services-such as the needle exchange program and organizing events for Santa Barbara’s gay community-were not impacted by the cuts, but the nonprofit’s rules prohibit the organization from drawing on these causes to supplement its HIV/AIDS services.

David Selberg, the organization’s executive director, has been scrambling to regroup since the cuts, which kneecapped the biggest-budgeted HIV/AIDS-benefitting nonprofit between Los Angeles and San Francisco. “We went into panic mode,” he recalled of the day he received word. In Selberg’s estimation, the 35-year-old organization was reduced to what it was when he joined in the mid ’80s, when medical science and the world at large understood comparatively little about AIDS. Before the cuts, PPF had two nurses and four case workers, but now the staff has been reduced to what it was back then: one full-time nurse and one full-time social worker, who now must shoulder the work of their departed colleagues.

Selberg has been pushing hard to form coalitions among the California communities hurt the worst by the cuts. “Whatever money is left will go to the major metropolitan communities like San Francisco or Los Angeles or to the small, rural communities like Butte County,” he said. That leaves midsized communities such as Santa Barbara, Ventura, and San Luis Obispo to fend for themselves, so Selberg is organizing a letter-writing campaign targeting higher-ups at the California Health & Human Services Agency to draw their attention to Santa Barbara’s plight. (A form letter is available at pacificpridefoundation.org.) Critics have also alleged that Schwarzenegger’s veto-which nixed $489 million from a long list of state-dependent departments-violated California law, but it remains to be seen whether these arguments have merit.

The reduction of PPF services, however, does not mean an across-the-board elimination of all HIV/AIDS services for the entire county. As explained by Dan Reid, Public Health assistant deputy director, the county cares for 220 infected people, offering primary care and specialty services. “Although all program elements will be impacted, we believe we will still be able to deliver high-quality medical care for those who need it,” he said before explaining that though the county does not offer the breadth of services that PPF does, it does have its own outreach, testing, and counseling programs. However, the PPF cuts still mean a hard blow for the county. “[PPF] has been instrumental in reducing the number of HIV and Hepatitis C infections that would have occurred if that program weren’t in place,” Reid noted. “There will be people who fall through the cracks.”

Meanwhile, job titles now have little meaning for many PPF staffers. When asked, they pause and try to remember just how many jobs they now juggle. “It seems that anything that gets done here is a team effort,” said Cassie Chavez, a UCSB grad who has worked for the organization for just over a year. Chavez bemoaned the loss of money PPF used to buy HIV/AIDS test kits, which previously could be used by anyone in the community to test their status anonymously and get results in 20 minutes. No longer. With limited money, the kits, which cost $12 each, are rationed, with preference going to higher-risk people-those who had unprotected sex with someone they knew to be infected, for example. Between July 2008 and June 2009, staffers administered around 1,600 HIV tests, but the numbers for this fiscal year will be considerably lower. Much to the staff’s distress, someone coming in soon after a questionable one-night stand now has to be turned away. “I hate saying it, but now we have to see if someone’s worth it,” said Chavez. (Those needing to check their status can still get tests at locations such as Planned Parenthood, which will begin offering rapid tests in November, as well as at area clinics.)

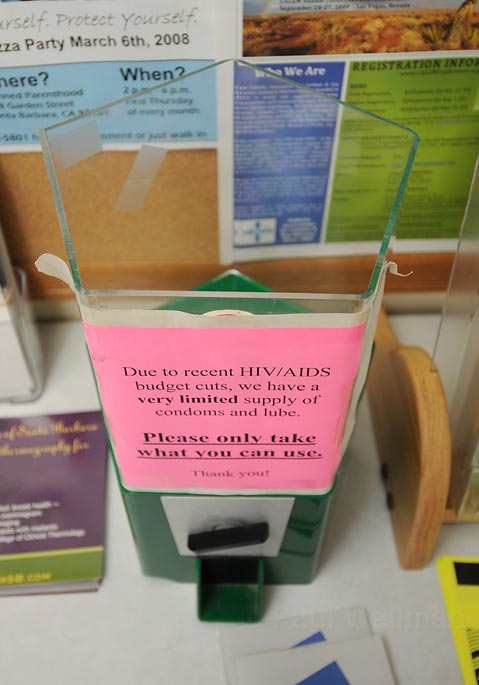

And perhaps the clearest indicator of the situation’s direness is the free condom jar, which now sits empty at the office’s front desk. The organization simply lacks money to buy the most basic tool of HIV/AIDS prevention. If anyone pops in, asking for free protection, staffers can only apologize and hope that efforts to solicit donations by condom manufacturers eventually pay off.

The prevailing hope is that this year’s annual AIDS Walk, held October 3, will bring in enough money to ease some pain. Last year, the event raked in $75,000 for the organization. That’s small potatoes compared to the $600,000 lost as a result of Schwarzenegger’s cuts, but PPFers nonetheless maintain that if anyone has considered participating previously, this year would be the one to sign up, to walk, and to truly make a difference.

Below PPF’s second-story office on East Haley Street exists a food pantry where the HIV- or AIDS-afflicted can go to “shop” for food and other items. Aside from the lack of a cash register, the market appears to be a reduced-scale reproduction of an actual grocery store, complete with miniature shopping carts. One shelf, however, features a conspicuously extensive collection of anti-diarrheal medicine, which should indicate to those in the know the true purpose of this particular pantry: Such medicine is often needed to counteract the side effects of the pill “cocktails” taken by AIDS sufferers.

Bill-a longtime PPF client and volunteer who declined to give his last name-praised the food pantry as being triply useful for those helping people to cope with the disease. The disease symptoms and medication side effects he suffers with on a daily basis include dementia, neuropathy in both feet, and blindness in one eye. “I can walk, but I have to break to catch my breath,” he said, explaining that the physical act of trudging through a large grocery store can be intimidating. Thus, the pantry allows him to pick up necessities without straining himself or his limited budget. Furthermore, the promise of food-free to those who need it, but carefully rationed-brings in clients who might not otherwise check in with PPF staff regularly. Thirdly, the pantry visits allow disease sufferers a social outlet. “For many, this is their only outing,” Bill said. “And they can talk to people who understand what they’re going through. : You can’t go up to a stranger on the street and talk about your HIV treatment.”

The cuts, however, necessitated the termination of the pantry’s coordinator as well as the reduction in hours of operation from three days a week to now just Tuesday and Thursday. According to Bob Blackford, also a client and volunteer, bad omens like this one create a “visceral anxiety” for the people who depend most on PPF. Like Bill, Blackford is a “long-term survivor,” meaning he has outlived a great many others who contracted HIV around the time he did. “People worry,” Blackford said. “They think: Who’s going to help that person get to the doctor? Who’s going to help them when their prescription gets screwed up? What’s going to happen to me?”

As both volunteers and clients, Bill and Blackford are uniquely aware of how the cuts create risks beyond the fate of the pantry. “If we can’t get the testing back, the risk is just staggering for everyone in the community,” noted Blackford. Bill agreed. “When I heard that [PPF] was closing down testing, I knew that was bad news for the community as a whole,” he said. “A lot of heterosexual people get infected, too. You have to be careful, no matter what you do.”

“We lost touch because I don’t follow her anymore,” explained PPF’s Ramiro Diaz of the HIV-infected mother who gave birth in August. He spoke at PPF’s Santa Maria office, a two-story building whose upper floor has been vacated in the hope that it can be rented out. For Diaz, the notion of no longer being able to monitor clients is difficult for many reasons-the risk of post-birth mother-to-child infections among them. For example, if an infected mother doesn’t understand that she can’t safely breastfeed her baby, the nine months of work that went into protecting the child could be undone.

As North County case manager Cynthia Camacho noted, the region’s many Spanish-speaking clients face special obstacles. In addition to the language barrier, some simply may not be educated or accustomed to the rituals that must be adopted to fight a disease as serious as AIDS. Camacho recalled one mother who, upon being given the pills she’d need to protect her child in utero, did not understand that they had to be taken throughout the course of the day. Instead, the mother took the day’s allotment all at once until supervisors realized her mistake.

Perhaps most problematic about this particular group of PPF clients is a cultural attitude that tends to facilitate transmission of the disease. “People from Mexico don’t use condoms like people [who grew up in the U.S.] do,” explained Diaz. Camacho elaborated: “When you’re with somebody and you ask them to use a condom, it’s like you’re either saying that they’re dirty or you’re dirty. It can be insulting.” (Efforts to interview women who conceived children after they became infected were met with reluctance either from the women themselves or from male partners uncomfortable with their status being disclosed in a news article.) Consequently, women in this particular demographic can become infected even if they’re in long-term relationships with one man, if he engages in high-risk behavior such as unprotected sex with other men or women and does not tell her. The worst possible result of this deadly silence about the disease, of course, would be transmission to the entirely innocent children.

Diaz and Camacho said they worry about how well PPF could service future clients under the new financial constraints. Diaz echoed the sentiments of many of his South County colleagues, saying, “I put my hope in the AIDS Walk this year.” Camacho looked even further into the organization’s financial future. “They’re predicting it may be even worse next year. It’s really scary. We’re struggling as it is to stay above water,” she said. “I don’t know what we’ll do if next year is worse.”

4•1•1

Pacific Pride Foundation’s 19th annual AIDS Walk begins at 10 a.m. on October 3 at Leadbetter Beach. Sign up at pacificpridefoundation.org.