Crossing the Desert

Musings on the Way Home to Santa Maria

It’s late afternoon and I’m on the Amtrak bus headed home to Santa Maria and my wife and children whom I miss something awful. I left Tucson last night, 14 long hours ago, on the train. Last Friday, while in Tucson, I attended a trial during which a Federal Magistrate told Walt that she intends to give him 25 days in prison for littering. Walt will have to miss a month of divinity school, where he is training to become a Christian minister.

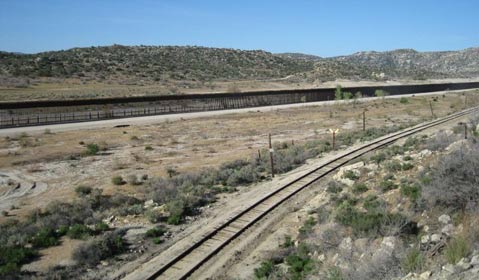

Walt was caught putting jugs of water in the desert for Mexicans walking for days, crossing our border illegally. Hundreds of young people, including women and children, die each year of dehydration, walking the desert trying to get to the jobs we offer them here. If you leave water for them in the desert so that they won’t die, you risk going to prison for littering. Three days after the trial, I joined a few people in the desert to put out gallon jugs of water. I didn’t get caught.

I am approaching Santa Maria now and looking out the window of the Amtrak bus I see the sprawling fields and the folks working there. They didn’t get caught either. They are the ones who made it. The ones we hire because they are so good at what they do, and because we don’t need to pay them too much, or provide them with medical insurance. The hospital will take care of them if there is a real emergency and then we can complain that they are sucking our resources dry as a desert.

Tomorrow my wife and I will join Guadalupe, her husband Jesus, and their daughter Juanita (our Goddaughter) for a farewell lunch. None of them, however, will fare very well. Guadalupe is 24 years old and in two days she will be leaving to return to her home in Oaxaca, Mexico. She is going home to die. She will take with her the terminal ovarian cancer she has been struggling with since she was pregnant, and she will take her now almost two-year-old daughter whom she refused to abort when she was offered chemotherapy. Her husband Jesus will stay here and continue working in the strawberry fields. The family will let Jesus know when his wife dies and he will send money to Mexico for his daughter. He will have to say goodbye to Guadalupe here because he can’t go with her. He wouldn’t be able to cross the unforgiving desert again to get back, especially since he will be his daughter’s sole surviving parent and provider. My heart is breaking for them all.

Some people don’t care about Guadalupe or Jesus or their daughter or all the other folks who risk dying in the desert to get the jobs we offer them. Don’t give them water. Better if they die. They are not supposed to be here anyway. So what if Guadalupe’s family is torn apart in her final days-they’re not supposed to be here anyway. We lure them here with jobs, and we get a great deal on strawberries, but they’re not supposed to be here anyway. After all, they are illegal-certainly way more illegal than the people who hire them.

Some people feel like we need our agricultural workers and should welcome them rather than reject them. Some people feel that we should make sure that our field workers are safe, well paid, and cared for medically; that their children are God’s children, the same as ours. Some people think that it is absurd that to save a life with water should be called littering, and think that Jesus should be at his wife’s side at her death and still be able to come back and provide for his daughter.

I suppose all of us identify with some people. But which people we identify with can make the difference between a world of love and peace or a world of exclusion and suffering, not to mention the health of our hearts and souls. Perhaps the new year is a good time to consider the occasional tension between laws and compassion, and which we want to opt for.