Human Rights Superman

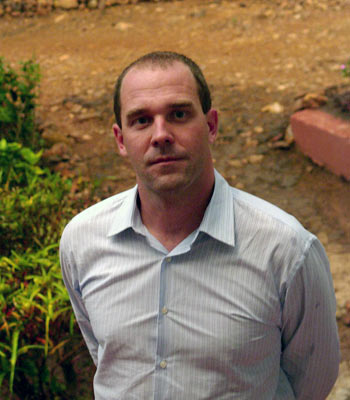

UCSB Grad Peter Bouckaert Is Changing Human Rights Work, One Crisis at a Time

On September 28, while Americans were worrying about health-care reform and a troop surge in Afghanistan, the citizens of Conakry-capital of the West African country of Guinea-were being brutally massacred by their own government. More than 50,000 people had converged inside their national soccer stadium for a peaceful protest against the ruling military junta. Suddenly, the presidential guard, the notorious “red berets,” fired their AK-47s point-blank into the crowd until their clips were empty. Those left standing were attacked with bayonets and batons, and more than two-dozen women were raped, most repeatedly, some penetrated by weapons. When the tear gas settled, at least 157 people were dead, nearly 1,500 injured.

If it had been up to the Guinean bad guys-who tried to secretly bury more than 100 bullet-ridden corpses at an army camp-the world would never know this atrocity occurred. That’s where good guys like Peter Bouckaert come in. While the troops were continuing to terrorize the city, Bouckaert, the director of Human Rights Watch’s emergency research team, hit the streets of Conakry on October 10, interviewing witnesses and victims to determine what really happened. “Atrocities are not new to us, but what we found in Guinea shocked us,” said Bouckaert. “We were shaken by the sheer brutality of what happened.” On October 27, Human Rights Watch released its findings that the attacks were premeditated, which resulted in France suspending military ties to its former colony, the United States issuing a stern decree, the European Union enacting an arms embargo, and FIFA moving a World Cup-qualifying match to Ghana.

That, in a gritty nutshell, is exactly what Bouckaert’s been doing for the last 10 years. In the past six months, Bouckaert’s travel itinerary included a trip to northern Iraq to assess the growing tensions between Kurds and Arabs, and a jaunt down to Yemen, where government and rebel clashes have hurt innocent civilians and threatened to further destabilize the region. Six days before the Guinean bloodshed occurred, he made a much more restful stop in Santa Barbara, where lunch guests at Montecito’s Birnam Wood Country Club listened intently to Bouckaert’s tales of torture, torment, and hope.

Why Bouckaert came to Santa Barbara on September 22 is twofold: One, he’s a graduate of UC Santa Barbara, where he got a degree in black studies, fought for diversity on campus as an elected student representative, and was integral in getting then-chancellor Barbara Uehling to step down; and two, Santa Barbara boasts one of the most energized support networks for Human Right Watch (HRW), rivaling cities 10 times its size and thereby able to bring HRW superstars to town.

What makes his story worth hearing, however, is that the Belgian-born, Bay Area-raised, Stanford Law-educated Bouckaert almost single-handedly has changed the business of human rights work by pushing his organization and others to evolve beyond the traditional postwar note-taking role and step directly into conflicts in hopes of stopping the bloodshed sooner. “It seemed like we were missing an opportunity to stop the killings,” said Bouckaert at the Birnam Wood lunch, remembering back to his trip to Kosovo in the 1990s, when he helped draw worldwide attention to the ethnic cleansing underway. “We had the choice to act in the face of the knowledge we’d collected or to stand by and knowingly let atrocities take place.”

Since then, Bouckaert’s become a familiar face in the world’s hottest spots-from Chechnya to Burma, the Congo to Gaza-and his reports have curtailed the use of child soldiers, informed international criminal cases, caused countries to reconsider cluster munitions and landmines, spurred manhunts for abusers, and put every mad dictator and rebel leader on high alert. Although the world’s laundry list of bad guys seems to grow each day, Bouckaert is making sure that their human rights abuses hit the front pages immediately and result in real punishment.

“The traditional methodology was waiting until the conflicts had subsided and it was safe enough to go in,” explained Vicki Riskin, a veteran screenwriter and Montecito resident who’s been involved with HRW for 20 years, and currently serves on its international board and as chair of the Santa Barbara committee. The organization, which originally was founded in 1978 as the Helsinki Watch to monitor the Soviet Union, quickly expanded its work to encompass the globe. “Peter pushed the organization to develop a small emergency team, which could be deployed within 48 hours to where the conflict was raging and to get the truth out. : He’s literally saved many, many lives.”

The Path

Peter Bouckaert’s lilting accent comes from his childhood on a farm in Belgium, where his father, who owned biotech companies, had played a significant role in the Flemish nationalist movement of the 1970s. In the mid 1980s, the elder Bouckaert sold one of his companies to a Bay Area firm and came to California to oversee operations. On what was supposed to be a two-week summer vacation, his father told the 15-year-old Peter, while driving across the Bay Bridge, that the family was going to move to the Golden State. “I had always been into the sea and fishing and ocean life,” said Bouckaert recently over the phone from his home in Geneva, Switzerland, where he lives with his wife and two children, “so living in the Bay Area was just wonderful.” But adjusting to a new country as a teenager was tough-“it was the perfect age to fall in with the wrong crowd,” said Bouckaert, admitting that he “had a little pot-smoking problem” that got him kicked out of two high schools.

But a dedicated teacher got him focused, and Bouckaert came to UCSB in 1989, where he planned to study marine biology. While he quickly realized he’d be spending more time in the lab than on the ocean, he simultaneously was developing a growing interest in civil rights. This led him to become one of the few white kids to major in black studies. “It wasn’t just about African-American history,” recalled Bouckaert, who also ended up being political chair of the 100 Black Men group and the historian of the Black Student Union. “It was much more about promoting diversity on campus and trying to create a campus that was really a multicultural environment. Santa Barbara is often not multicultural, so we felt it was important to create that space and those opportunities-not just for the African-Americans and Latino students, but for the health of the overall campus.”

According to former professors, his advocacy went far beyond rhetoric. “Black students knew that they could trust this man, that he was real, that he was about justice for everybody, about fairness, about uplifting the standard of living for everybody-and nothing would stop him,” said Claudine Michel, a black studies professor originally from Haiti who quickly bonded with the similarly foreign-born Bouckaert. “He’s a very kind, warm individual, but he’s willing to put his life on the line.”

Retired sociology professor Bill Felstiner, who taught Bouckaert under the now defunct Law & Society program, was equally impressed. “He was the most spectacular undergrad I ever taught,” said Felstiner, who also taught at UCLA, USC, and Yale. “It was clear he had the social conscious of an adult.” More memorably, Bouckaert didn’t disappear after graduation. “He actually kept in touch,” said Felstiner, who has since founded his own nonprofit called the Chad Relief Foundation. “In a big, mass-educational factory like UCSB, that’s rather unusual.”

Bouckaert’s activist spirit found a home in campus politics, where he was elected as an Associated Student representative. In addition to starting outreach programs in Los Angeles ghettoes and visiting prisoners in jail, Bouckaert led the charge to get then-chancellor Barbara Uehling to resign. “She was way out of touch with the campus community,” said Bouckaert. The faculty eventually took a no-confidence vote in her leadership, and she stepped down.

“Peter was instrumental in putting pressure on the institution to live up to its ideologies,” recalled Michael Young, then and now the vice chancellor of student affairs, a role that involves monitoring campus demonstrations and interacting with student government. Though Young’s office occasionally was at odds with Bouckaert’s activist agenda, their relationship never soured. “What I loved about working with Peter was that, even if you were in contention, you could always talk to him,” said Young. “If you treated him with respect, he returned that respect.” Upon graduation, Young had the honor of presenting Bouckaert with the Storke Award, given out each year to the UCSB student who most exemplifies scholarship and service.

Bouckaert recalls his UCSB years fondly. “In the popular imagination, UCSB is just known as a party school,” he said. “For me, it was much more than that-it was a serious academic environment. I got very close with a lot of my professors, and I enjoyed the fact that I could study on the beach.” And he still uses quite a bit of what he learned during his Gaucho days. “My teachers taught me that if you want to play a leadership role on civil rights or human rights issues, first and foremost, you have to educate yourself-you’re dealing with complex issues and you have to make sense of them,” he explained. “They did instill a work ethic in me in terms of preparation, which is still very much with me. It’s not a game when you’re talking about the kind of massacres and crimes we document.”

Bouckaert went straight to Stanford Law School, where he found himself surrounded by future corporate lawyers. “I felt like a freak among guys in suits,” he said. He decided to take off a year and applied for an internship in South Africa, where the selection committee hired him because they thought he was black. He found this out from one of the South African women on the committee who would later become his wife. “Her first words to me when I finally met her were, ‘You’re not black,'” laughed Bouckaert. “She was quite shocked.”

In South Africa, he worked for a legal resource center that fought against apartheid, argued death penalty cases, and even wrote legislation to create the now widely celebrated Truth and Reconciliation Commission. “I was one step removed from Nelson Mandela,” said Bouckaert. “As a young kid out of the first year of law school, it was a really empowering experience.” He returned to Stanford much more comfortable, explaining, “I had a little more experience to guide my career toward where I wanted to go.”

The Work

When Bouckaert graduated from Stanford and got a fellowship with Human Rights Watch, the organization was still operating very much like human rights groups had for decades: entering conflict zones once the bullets stopped flying, oftentimes with government approval; interviewing victims and witnesses for weeks on end; and publishing lengthy documents read mainly by diplomats many months later. But when he landed in Kosovo in the late 1990s and saw the death squads of Slobodan MiloÅ¡eviÄ and his enemies, Bouckaert realized the protocol had to change. “It was high time that the human rights movement moved beyond dealing with prisoner and torture issues, and stepped into the warfront and developed methodologies to help save lives while people are being killed rather than write about them later,” explained Bouckaert. He gave his findings to a New York Times reporter, and when the story hit the paper’s front page, it was only a matter of time before the president Bill Clinton sent in the warplanes.

“He really was the only human rights researcher there,” said Jane Olson, who’s worked for HRW for 22 years and has been the organization’s chair for the past six-and-a-half years. “There were no journalists. He was the eyes and the ears on the ground for the whole world.” Bouckaert repeated this approach during the Second Chechen War in 1999. “He was on the ground, recording how many people were killed, who the perpetrators were, and so on,” said Olson. “That seemed to stop the revenge killings.”

These bold but effective methods led to the creation of the emergency research team in 1999, which was staffed solely by Bouckaert until 2004 and today is usually the first international observer group to enter a country in conflict. It has become increasingly more essential work as newspapers-historically, the world’s watchdogs on atrocities-began shutting down their foreign bureaus worldwide. “Our emergency researchers have stepped in to fill that vacuum,” said Olson. “We used to publish exhaustive, research book-length reports on human rights abuses. Now, we try to get out the facts as fast as we can verify them.”

Consequently, the organization’s reports are now “briefer and punchier and more immediate,” said Olson, who lives in Pasadena but owns a home on the Montecito waterfront. She added that HRW’s audience is no longer solely diplomats, but also everyday people keeping up on global affairs via the Internet. HRW now publishes as many as a dozen reports per week and countless news updates; in December alone, the organization published 11 full-length reports-on Guinea, Yemen, Libya, Brazil, India, the United States, and elsewhere-and issued another 60 calls to action on its Web site, hrw.org, many involving photographs and video footage. The organization has learned to release reports to coincide with and hopefully influence ongoing diplomatic efforts, whether it’s a landmine conference in Cartagena, Colombia, or Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s recent trip to Asia. “We want to have an impact on the dialogue,” said Olson.

While both diplomats and newspapers are ever-ready to welcome the next Human Rights Watch report, that doesn’t mean Bouckaert’s job on the ground is any easier. It’s often very dangerous work and requires occasional clandestine-though never explicitly illegal-tactics. As an unassuming, friendly fellow wearing a steady smile, Bouckaert fits the bill perfectly. HRW’s Riskin recalled Bouckaert’s ability to work in Burma, one of the world’s most security-conscious regimes. “There’s something about the way he operates that makes him not someone who gets noticed,” she explained. “He carefully plans out how he is going to operate to get the truth and to get it from the right people, without ever putting himself, and, even more importantly, without putting the people he’s interviewing at risk.”

He’s so good, in fact, that some oppressive regimes have begun to limit or ban human rights monitors altogether. “This is not just a pattern that affects Human Rights Watch,” said Bouckaert. “Even more so, it affects the local human rights organizations around the world.” Because of that, Bouckaert explained, “In a lot of places, we have to go pretty deep undercover to be able to do our work. : We don’t go in without our visas, but we don’t always explain the full reasons of why we’re there.”

Whether undercover or announced, separating fact from fiction in a war zone remains challenging. “We realize that war is an extreme form of politics, and in politics, people need to believe their part of the story, so they try to manipulate it,” explained Bouckaert, who is careful to report abuses on each side of every conflict. “We’re not gullible investigators. We go into these situations with a lot of skepticism.” When they find a victim or witness, they sit down for an hour to two and focus on the things they’ve personally seen and then cross-confirm their findings with others. If the information cannot be verified, it’s not included in the report. “In Guinea,” Bouckaert explained, “we have a lot of additional information that we’re not putting in the report because it’s not cross-confirmed.”

That level of detail is critical, explained Bouckaert. “At the end of the day, we’re investigating criminals and we constantly realize that, unlike journalists, we may very well end up testifying about what we’re investigating,” said Bouckaert, who’s had to use his reports multiple times in court to prove that those accused were guilty of their crimes beyond a reasonable doubt. And it works. “We’ve won every single case,” he said proudly.

The Future

Right now, if Peter Bouckaert hasn’t already flown into the current catastrophe, he’s just waiting for the phone to ring. “That’s the scary part of this job,” he admitted. “You never know where something is going to go off.” But even if no new dictators open fire on protesters, there are plenty of existing human rights disasters to keep Bouckaert and his team busy for years.

Based on recent travels, Bouckaert’s particularly concerned about what he calls a “tinder box” in Yemen and worried about what will happen in Iraq when the United States pulls out, for he fears war between the Kurds and Arabs in the north over oil resources. “These are the kinds of issues that the Obama administration is struggling with,” said Bouckaert. “It’s great that we have a change in vision and a willingness to engage the world and be part of the solution rather than part of the problem, but these are very serious challenges.” Though he has no silver-bullet solution, he does believe “we’ll be a lot better off if we focus on building peace and true friendships around the world rather than just focusing on military confrontation, which is a very blunt force.”

And there’s plenty the everyday Santa Barbaran can do to foster the future, said Bouckaert. “I hope that we all find a way to contribute to building a better world for tomorrow,” he explained. “It actually adds value to our lives to try and make a difference in this world. Each person has to find their own path to do that. It doesn’t matter if you are working for diversity at UCSB or for gay and lesbian rights, or helping the homeless, or going out to a war zone. It’s all about making a little difference, whether it’s about environmental change or human rights.”

Bouckaert’s entire life has been inspired by his brother, Thomas, who died in a car accident when Peter was nine. Though it’s nearly 30 years later, Bouckaert says that loss “is still very much with me,” and it enables him to feel extra empathy for the people he interviews, some of whom have just lost their entire families hours before. “What Thomas’s loss meant most to me is that it’s important to live a life worth living,” said Bouckaert. “Mine may sound like a suicidal path to engage in, but to me, this is a life worth living. I don’t jump in front of bullets, but we take some calculated risks to save lives and to make sure their stories are heard.”

4•1•1

See the Human Rights Watch website for more information.