Are Primary-Care Doctors Going the Way of the Dodo?

Frontline, General Practice Doctors Are Closing Their Doors Left and Right

In 2003, after years of bouncing from one primary-care doctor I didn’t like to another, good fortune led me to the offices of Naomi Parry, an earthy, fifty-something internist with a maternal streak. She earned my loyalty in a snap. As a fellow working mother, it felt safe to kvetch about life as well as health, and she didn’t judge my penchant for alternative medicine. What a find.

I loved having my own doctor, someone who knew me and whom I could call in the spring when early blooms turned my eyes into a waterworks show, or when a sore throat lingered. Sadly, before the year was out, Parry announced she was closing her practice. The hours it demanded had become inordinate, she said, and she needed to spend more time with her family.

Darn.

A year passed before I began my search for a replacement. A friend recommended Anna Hays, also in solo-practice. She didn’t take insurance, but if I paid with plastic, her office would bill my insurance and I would get a percentage of the fee reimbursed. At the time, it was doable. Hays was another winner; everything I could want in a doctor: sharp, funny, irreverent, personable, and she spent an hour with me once a year for a physical. Then, in May 2008, when I was in for an ear infection, she said she too was closing her practice. She’d been offered a lucrative position caring for inmates at a California State Prison, where healthcare has been so inadequate, the entire system was put under the supervision of the court. Handing me a short list of Santa Barbara internists she recommended, we said goodbye.

Shucks.

Was losing the two best physicians I’ve ever had in four years just bad luck, or is there something unhealthy about Santa Barbara’s healthcare system? A few phone calls provided the answer. Santa Barbara internists and family practice physicians in solo-practice (as opposed to doctors on staff at Sansum or the Neighborhood Clinics) are closing their doors left and right these days. And if they’re not, they’re either thinking about it or transitioning to the “concierge” system-a lucrative form of practice in which patients pay in the neighborhood of $1,800 a year, on top of the usual co-pays and deductibles, to have nearly immediate access to their doctor. A cool deal if you’ve got the dough.

Going, Going, Gone?

Whether practicing in Santa Barbara or Des Moines, frontline, general practice doctors are under enormous pressure today. Because they’re paid the least of all physicians, they have to see more patients in a day and work longer hours to make their businesses fly. Only 2 percent of graduating medical students are choosing to become primary-care doctors, according to recent surveys. The trend is alarming the medical community and politicians because these are the doctors who catch illnesses when cures are simple and cheap. The healthcare overhaul bill recently passed by three committees in the House of Representatives provides some scholarship and loan repayment programs to beef up the nation’s supply of doctors, nurses, and physician assistants. Senator Max Baucus (D-MT), chair of the Senate Finance Committee (which still is trying to hammer out a bipartisan healthcare reform bill) is reported to be very aware and concerned about the issue as well.

Good healthcare starts with every person having a comfortable, open, long-term relationship with their primary-care doc. Ideally, throughout time, the doctor’s knowledge and understanding of an individual allows her or him to pinpoint problems when they’re a mere blip on the radar screen and to steer the patient toward a healthier lifestyle. But in an illogical, quintessentially American twist, the primary doc’s role is undermined because they’re paid less than the specialists who perform the technological feats necessary to fix things after they’ve become life threatening.

The problem is worse for Santa Barbara’s primary-care doctors because Medicare’s formula for calculating physician pay is based on the economies of lonesome, rural Central Valley counties like Yolo. Combine the extremely high cost of doing business in Santa Barbara, this lopsided Medicare pay rate with the fact that private insurers base their physician pay schedule largely on what Medicare is offering, and you get the slow but steady exodus of good doctors from our area.

A June 2009 study by the California HealthCare Foundation reported that Santa Barbara County has 58 primary-care doctors per 100,000 people, with 60 per 100,000 considered adequate. It also found the county has 125 specialists per 100,000 people. Similarly, a study commissioned by Cottage Health System found that by 2011, this county will have 20 fewer general practice doctors than it needs.

Why should we care, especially if we’re healthy and don’t use the services of a doctor much? Because communities with a good supply of primary-care doctors are healthier. They have lower mortality rates overall, lower mortality rates for heart disease and cancer, fewer hospitalizations, fewer ER visits, and use less healthcare dollars.

Across America, primary-care doctors in multispecialty clinics like Sansum gross around $174,000 annually, according to the Medical Group Management Association. (Sansum wouldn’t reveal the average salary of its primary-care docs, but given the Medicare payment method, it’s definitely less.) In defense of physicians’ salaries, Sansum CEO Kurt Ransohoff said people should remember that doctors generally don’t receive a paycheck until eight or 10 years after graduating college, and that they have significant debt burden. “And there’s a lot of responsibility,” he said.

The average solo-practitioner here nets about that of a veteran teacher or a high-ranking cop-minus the retirement and health benefits. What’s wrong with that? Nothing, if you’re a regular person putting in a regular 40-hour week. But consider the eight to 10 years doctors spend getting educated, the six-figure medical debt they’re paying off, the nights and weekends they have to be on-call, and the cost of raising kids here, and the appeal of such a salary shrinks.

The Santa Barbara doctors I interviewed who closed their practices told stories of exhaustion and feeling helpless as income slipped and hours and overhead piled up. Most of them considered becoming concierge, but couldn’t reconcile the exclusivity of it. Anne White, a soft-spoken, redheaded osteopath with two children, opened her solo-practice in 2007 after being at Sansum Clinic for six years. The first sign of trouble came from Medicare. Consistently four or more months behind in payments, it was six months before she saw her first reimbursement check from the program. Then, because private insurers reimburse low and slow as well, she required her patients to pay for their care upfront, then billed their insurance as a courtesy. But some patients didn’t know or understand their insurance policies, and were disappointed or upset when they discovered their visit wasn’t covered.

Another obstacle was overhead: rent, malpractice insurance, utilities, taxes, fees, equipment; the list was infinite, White said. “[Having] someone to do payroll for one employee was costing me more than $100 a month,” she said. “It was awful. I couldn’t believe it.”

White’s husband was recovering from surgery for part of the first year of her practice, so the family had to rely on her income. She took a job as a hospitalist at Goleta Valley Cottage Hospital and Cottage Hospital to supplement. (A hospitalist is a primary-care doctor who replaces a patient’s primary-care doctor once he or she is admitted to the hospital, because many internists and family practice physicians are too bogged down with back-to-back office visits to straddle both environments.) But it meant she was often working through the night. Just when her husband recovered, the recession hit Santa Barbara, drying up trade jobs. Bringing home an average of $2,000 a month, or $24,000 a year before taxes, just wasn’t keeping the family afloat. In November 2008, she had to acknowledge it wasn’t working. “I still had no income and realized that if I stayed in business, I was going to be broke and lose my house,” she said tearfully.

One Santa Barbara doctor explained that if a primary-care doctor accepted private insurance, no matter the plan, the profit margin was pretty much set. The only way to increase revenue was to work more-see more patients. But this doctor, who didn’t want to give her name, drew the line at 22 to 23 per day. “I would not go to seeing a patient every 10 minutes,” she said. “If you’re seeing a patient every 10 minutes, at the end of the day, are you going to remember which antibiotic you chose, let alone whether it was contraindicated with the other meds on their list?”

So she began to cut corners. She became her own bookkeeper, hired a physician assistant (PA). She bought a bone-density scanner, started a medically supervised weight-loss program. None of it helped. The only salary she could cut was her own, she said, and that she stubbornly refused to do. “I spent 10 years getting an education. Ten years where I wasn’t making anything,” she said. “You have a certain expectation for what your education will get you.” She paid herself $140,000 a year, gross-about $88,000 net-but, ultimately, she had to take bank loans to do it. Then, last summer, looking at the debt she’d accumulated, she threw up her hands and moved out of state.

Another Santa Barbara internist who also wanted to stay anonymous, said in 20 years of solo-practice here, his income has always hovered around $43,000 net. From that, he must buy his own health insurance and save for retirement. This doctor closed his office practice several years ago but continues to see patients in a variety of other settings.

Joe York earned more than most solo-practice internists here-about $90,000 a year-but his patients consisted of folks with advanced and complicated illnesses like diabetes and heart disease, which kept him working 80 hours a week: 12-18 hours a day, five days a week and to the hospital on weekends, he said. A sizable percentage of his time was taken up by paperwork, though, getting treatments authorized, then reauthorized again and again. In 2003, he too gave up trying to make it work and accepted a job as a hospitalist at Marion Medical Center in Santa Maria. After doing so, he said he couldn’t give his practice away. “I think healthcare in this country is a real issue and a nightmare, actually. And I don’t think it’s going to get better no matter what we do.”

Other primary-care doctors who’ve closed their practices recently include Mary Ferris (who is now medical director at UCSB’s student health services), Tom Kennedy, and Anya Consiglio.

What Can Be Done?

Cottage has convened a committee to take a serious look at the primary-care doctor shortage, among other healthcare issues. Tom Allyn, a Santa Barbara internist and nephrologist, is the head of this Physician Hospital Alignment Workgroup. It’s exploring solutions as well as considering the possibility of Cottage merging with the financially struggling Sansum clinic. It consists of the doctors in leadership positions at the three hospitals and Cottage CEO Ron Werft. They’ve been meeting for more than a year.

Allyn emphasized that Santa Barbara isn’t unique in its growing shortage of primary-care doctors. He said that impending retirements would contribute to the problem. “We have a significant number of primary-care doctors who are certainly older than 50, and there are a bunch over 60.”

Some hospitals have resorted to hiring a supply of primary-care docs to put on staff. But that’s illegal in California. One idea that could work, according to Werft, is if the hospital formed a Management Support Organization, or MSO. It would provide support services to solo practitioners through economies of scale; things like malpractice insurance pools, staff support, electronic records support. All of that would take a bite out of their overhead burden. “Linking private practitioner records to the hospital would help the practitioners and improve care,” Werft said.

Another option would be to create a medical foundation like the famous Cleveland Clinic and Mayo Clinic. But the independent physicians who don’t choose to join a large staff of a big clinic fear they’d again be at a disadvantage.

Though recruiting is getting tougher, Sansum has no openings on its staff for primary-care doctors right now, and that’s a good thing for all of us. Still, not everyone wants to get their care in a large-clinic setting; some Sansum patients have found it hard to get in to see their own physician when they’re sick.

Will Santa Barbara residents soon have to choose between joining a concierge practice or going to Sansum for their primary care? Or will advanced practice nurse practitioners and physician assistants become the new gatekeepers, referring us to an MD only when they think our condition warrants someone with more education and training? Perhaps the answers will be found in the legislation being molded and shaped in the halls of the U.S. Capitol, or in television and talk radio rantings?

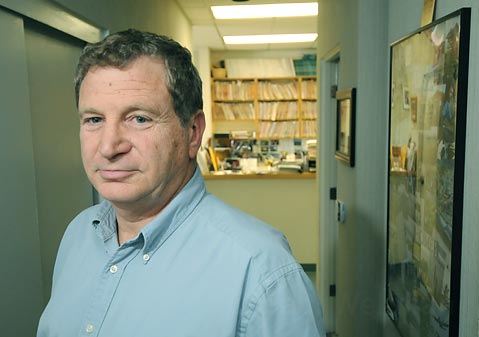

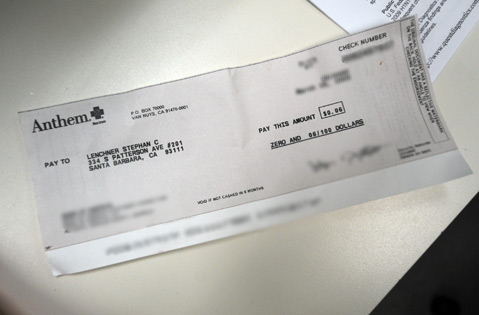

In the meantime, honor must be paid to the primary-care doctors who still are in the trenches, fighting the good fight, physicians like Melony Parent, James Kwako, and Stephan Lenchner. Lenchner is a family practice physician in Goleta who still heroically accepts all varieties of managed care, even HMOs. “The way I run my practice, if I need to spend more time with a patient, I can,” he said. “I don’t have anyone saying, ‘Did you see your 33 patients today?'”

However, things got even more difficult for him this spring when rent in his office building adjacent to Goleta Valley Cottage Hospital-a building owned by Cottage Health System-went up 31.4 percent. Lenchner had no choice but to take a side job-the specifics of which he will not reveal. “People see an MD at the end of your name and they think you’ve got it made,” Lenchner said. “But I have a friend who’s a teacher in L.A. who makes more than me.”

Melony Parent’s Goleta-based practice has morphed four times in 10 years, each time taking fewer and fewer kinds of private insurance plans. “I can’t make the PPO pay me more. I can’t make Medicare pay me more. All doctors can control is the volume,” said Parent, a single mom. Now, except for Medicare and Cottage Health System’s employee insurance plan, Parent is fee-for-service, pay as you go. “I’m like a hairdresser,” she said. “If she charges $100, you have to give her $100 before you leave the building.” But people aren’t getting their hair cut as much lately. Parent said more and more of her patients are coming in and announcing it’s the last time they can see her. They’re going to go to urgent care instead.

As for me, I need to find a new primary-care doctor. But, naturally, I’m worried that as soon as I get comfortable with him or her, they’ll announce a move to Georgia, where reimbursement is higher. Last May, I actually called Mara Sweeney, one of the internists Hays had recommended. Her receptionist told me the first appointment available for a new patient was at the end of August.