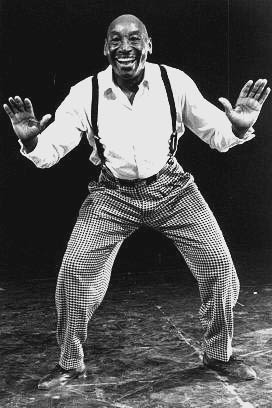

Lindy Legend Frankie Manning Returns to Santa Barbara

The King of Swing

Frankie Manning, ambassador of the lindy hop, dancer extraordinaire, and living legend in swing dance history makes his annual pilgrimage to Santa Barbara this weekend. As a pioneer of swing dance in the 1930s, Manning was at the epicenter of the movement that gave refuge to many Americans during two of the country’s greatest periods of disenchantment and strife: the Depression and World War II. Decades later, he was equally instrumental in the resurgence of swing in the ’80s and ’90s.

Manning was born in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1914. His earliest memory of dancing, which he recounts in his new autobiography, Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop, was watching dancers at the parties he would attend with his mother at her social club. By the time he was 12, his mother would let him dance if he helped her set up the party decorations, and he soon became known for his unerring musicality and uninhibited energy.

Manning began dancing more seriously at the Alhambra Ballroom in Harlem, and then at the Renaissance Ballroom, where he met and befriended many of the people who would become part of the first organized lindy dance troupe. Yet it wasn’t until 1929, when Manning began dancing at the Savoy Ballroom, that his dance career blossomed.

In the late 1920s, the swing movement was riding the wave of the intellectual and literary movement of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, and the Savoy was at the heart of it all. Significantly, the ballroom was the first racially integrated dance hall in the country. “The Savoy was practically half white and half black,” Manning said in a recent interview. “The only thing they wanted to do at the Savoy was dance. They didn’t care what color you were.”

Along with the club’s other premier dancers, Manning formed Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers in the early ’30s. The troupe brought the lindy hop into public awareness when it entered New York’s first annual Harvest Moon Ball, a city-wide competition that put lindy hop in the same league as more established dances like the fox trot, rumba, waltz, and tango. Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers were the only black troupe in the dance competition, and they swept up first-, second-, and third-place prizes.

Soon after the end of the war, however, swing went into a period of decline. By 1947, big bands were effectively over. Manning took a hiatus from dance, and for 30 years worked for the New York Postal Service. Swing was kept alive primarily by society dance bands, but the exuberance of Manning’s style of swing remained dormant.

In the 1980s, swing bands like the Stray Cats, Royal Crown Revue, and The Blasters renewed general interest in the art of swing. Those who were studying swing dance, Fincluding Santa Barbara’s own Jonathan Bixby and Sylvia Sykes, went on a quest to find people who could help bring back lindy’s exuberance. Their search led them to New York, where they found old-time swing dancers congregating at a club called Small’s Paradise. Members of Manning’s old troupe reportedly had to drag Manning back into the scene, and, at the age of 72, the king of swing started a second career as a dancer. Under his mentorship, the club evolved into a meeting place for neo-swing and lindy hoppers from all over the world.

Teachers Erin Stevens and Steven Mitchell from Pasadena and Bixby and Sykes from Santa Barbara have been credited with reintroducing swing to the West Coast, and for convincing Manning to teach again. Since his return to dance in 1987, Manning has choreographed for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, consulted on and performed in the Spike Lee film Malcolm X, served as a historical consultant for Mercedes Ellington’s Broadway musical, Play On!, and won a Tony for his choreography in the Broadway musical Black and Blue.

Every year, thanks to Bixby and Sykes, Manning comes to Santa Barbara to lend his expert tutelage to the city’s swing dancers. His warmth, talent, and infectious passion for dancing, coupled with his seven decades of experience, have made Manning a beloved and respected figure in the swing dance world.

4•1•1

For more information on Frankie Manning’s classes on September 15 and 16, call Jonathan Bixby and Sylvia Sykes at 569-1952 or visit jonathanandsylvia.com.