The Catch Heard ‘Round the World

Remembering the Day Al Gionfriddo Made Joe DiMaggio Angry, 60 Years Later

“We do not remember days,” wrote the Italian novelist Cesare Pavese. “We remember moments.”

The truth of that observation is borne out whenever people start talking about sports. Baseball has provided a treasure trove of memorable moments. Frequently, they are heralded by the crack of a bat: Bobby Thomson’s “shot heard ’round the world” in 1951; Bill Mazeroski’s blast that won the 1960 World Series; Carlton Fisk’s drive in the bottom of the 12th that kept the BoSox alive in 1975; Kirk Gibson’s theatrical four-bagger that launched the Dodgers to their improbable World Series victory in 1988-my gosh, almost two decades ago.

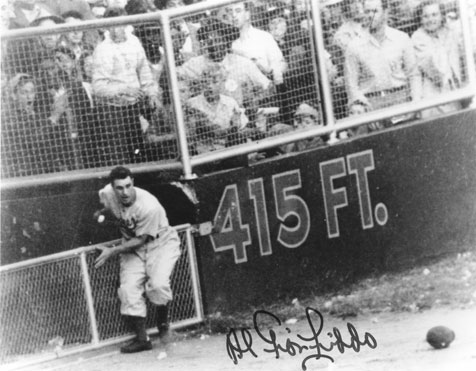

Six decades will have passed on Friday, October 5, since one of the most dramatic moments in the great Joe DiMaggio’s career-a clout that had “home run” written all over it but wound up in the glove of Al Gionfriddo.

Gionfriddo’s running catch against the fence at Yankee Stadium is a remarkably enduring bit of baseball memorabilia, outlasting the principals and most of the spectators at game six of the 1947 World Series. In the last few months, I came upon three accounts of the event-in a radio interview with the prize-winning journalist David Halberstam, who described it as his favorite sports memory; in a televised screening of the 1989 movie Dad, in which a dying Jack Lemmon, as the title character, tells his son about the catch; and in a recently published book, Jonathan Eig’s Opening Day, the story of Jackie Robinson’s first season.

The DiMaggio-Gionfriddo connection illustrates the equal-opportunity nature of baseball. The No. 8 hitter in the batting order may come up at the crucial time of the game; the obscure outfielder may be challenged to make the key play. In the ’47 series, there was no bigger star than DiMaggio of the New York Yankees and no smaller speck of a player than Gionfriddo of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

DiMaggio’s fame preceded their fateful meeting and lasted long after. Considered one of the greatest all-around players in baseball, Joltin’ Joe was immortalized in song, glamorized in his marriage to Marilyn Monroe, and commercialized as Mr. Coffee. Gionfriddo, on the other hand, was a journeyman who had a brief career in the major leagues but labored for years in the minors. He came to Santa Barbara in 1962 as general manager of a minor-league club, and stayed here to run a restaurant, Al’s Dugout in Goleta, and later became an athletic equipment manager at San Marcos High. In retirement, Gionfriddo was one of the better golfers to hit the links at Sandpiper and Alisal, his home course in Solvang. He was playing golf when he suffered a fatal heart attack on March 14, 2003, six days after he turned 81. DiMaggio had passed away four years earlier, exactly on Gionfriddo’s 77th birthday.

“Al was unpretentious,” said Sue Gionfriddo, the former ballplayer’s widow. She met him in 1968 when he was in the restaurant business but soon learned of his claim to fame. “Other people would make a big deal out of it,” she said. The doorbell at their home still rings to the tune of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.” On the 60th anniversary of the catch, Sue said she expects to “say a little prayer and play a round of golf.”

Al Gionfriddo grew up in Dysart, Pennsylvania. His greatest athletic asset was his speed. He was known as the “Dysart Deer.” He broke into the majors with the Pittsburgh Pirates and was traded to the Dodgers early in the 1947 season. In Opening Day, Eig writes that Gionfriddo was an outfielder “whom neither team wanted. At 5ʹ6Ê° and 150 pounds, Gionfriddo was the smallest man in the majors. The New York sports writers predicted he would soon be the smallest man in the minors.”

Twenty years ago, Gionfriddo told me he had felt a kinship with Jackie Robinson. The first black major leaguer in the modern era endured scorn not only from opponents but from some of his own teammates. He would not go into the showers until everybody else was done, Gionfriddo said, until one day he went up to Robinson and said, “Jackie, what are you waiting on? I’m not accepted any more than you are, but we’re part of this team. Let’s go.” It was common for players to recall kinder feelings toward Robinson than they actually had at the time, but Gionfriddo’s remembrance is supported by Eig’s research. The baseball historian writes: “Big-league culture was so dominated by white Southerners that even rough Italian kids from northern cities experienced shock and isolation upon arrival.”

Though he seldom played, Gionfriddo stuck with the Dodgers the rest of the season, and in the World Series he had two huge moments. As a pinch-runner in game four, he stole second base with two out in the bottom of the ninth, setting up an intentional walk to Pete Reiser, followed by Cookie Lavagetto’s two-run double that beat the Yankees, 3-2.

The heavily favored Yankees took a three-games-to-two lead into game six. They fell behind the Dodgers 8-5, but in the bottom of the sixth, DiMaggio came to the plate with two runners on base. Brooklyn manager Burt Shotton had just sent Gionfriddo into left field as a defensive replacement. He was playing near the line when DiMaggio stroked a tremendous drive toward the 415-foot sign in left center. Gionfriddo ran and ran, his hat flying off as he approached the fence and twisted his body to snag the ball in his gloved right hand. Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber made the call on the radio: “Back goes Gionfriddo. Back, back, back, back, back, back. He makes a one-handed catch against the bullpen. Oh, doctor.”

The normally unflappable DiMaggio had already reached second base, and he kicked the dirt in anger. “For a 13-year-old boy, it was a heady bit of stuff,” said Halberstam, who was in the crowd at Yankee Stadium. His vivid recollection of the catch was aired during a radio tribute to Halberstam after his untimely death last April.

Then there is Jack Lemmon on his deathbed in Dad: “This man [DiMaggio], who never showed any emotion, he was human after all. It took Al Gionfriddo to bring it out. Do you know what that means to me?”

“What?” asks his son, played by Ted Danson.

“In America,” Lemmon says, “anything is possible if you show up for work.”

The Dodgers won the game 8-6 thanks to Gionfriddo’s miraculous catch, but they went on to lose game seven and the series. Gionfriddo never played in another big-league game. Because of the power of his memorable moment, however, he happily avoided the fate inscribed by the poet Robert Frost:

No memory of having starred

Atones for later disregard,

Nor keeps the end from being hard.

FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS: The first cross-town rivalry game of the prep football season will take place Friday night when Carpinteria (2-2) hosts Bishop Diego (4-1). Both teams are coming off winning performances on the road. Santa Barbara High (3-1), suffering its first defeat at San Luis Obispo last week, returns home to face Pacifica. Dos Pueblos (2-2) will host Rio Mesa at San Marcos, while the Royals (0-4) seek their first win at Arroyo Grande.