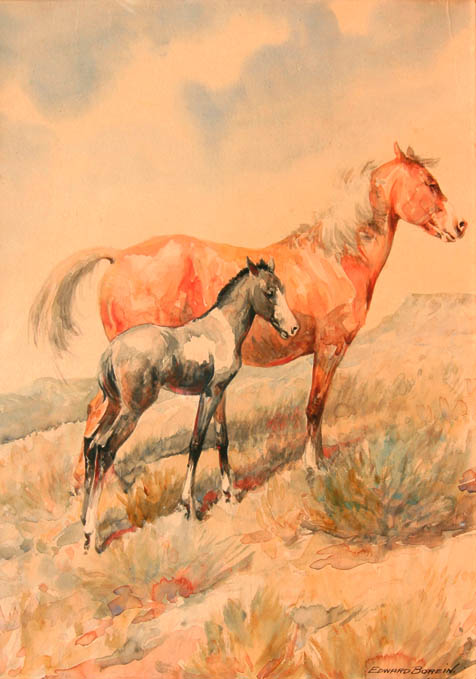

Edward Borein’s Archetypal Images of the Old West

Cowboys in Color

Exactly 100 years ago, a seasoned cowboy boarded a train for New York, hoping to fulfill his dream of becoming a professional artist. When he returned to his native California a dozen years later, Edward Borein was considered by many to be among the finest interpreters of the American West, an artist whose depictions of cowboys, Native Americans, and the rapidly disappearing culture of the Old West were valued as much for their accuracy as for their artistic merit. More than 40 paintings by this acclaimed artist are now displayed at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum in Coloring the West: Watercolors and Oils by Edward Borein, the largest exhibition of its kind ever mounted.

Borein, who died in Santa Barbara in 1945, was one of the last artists to capture the Old West from personal observation. Art historians now rank him alongside his boyhood idol Frederic Remington and his friend and mentor Charles Marion Russell as one of the most important artists to record this storied aspect of America’s past.

“Coloring the West allows us an unprecedented look at Ed Borein’s mastery of oil and watercolor paintings, giving us a window through which to view the American West as he experienced it,” said David Bisol, executive director of the Historical Museum. “With this major exhibition, the Historical Museum is reaffirming its commitment to give Borein the recognition he justly deserves as an artist who accurately interpreted an important part of our past.”

The opening of the exhibition also marks the launch of plans for the John Edward Borein Gallery of Western Heritage and Research Center, a project whose inception back to 1945, the year of the artist’s death. Convinced by friends that her husband’s legacy warranted preservation, Lucile Borein donated numerous works of art and personal objects-including Borein’s own collection of the best impressions of his etchings-to the Historical Museum, which has continued to collect the artist’s works throughout the years. A new, dedicated exhibition space and the associated research center will provide a showcase for the artist’s work, and will honor the national significance of Borein’s role in documenting the American West.

As one of few Western artists actually born and raised in the West, Borein occupies a unique position. Yet his transformation from cowboy to artist was not the fulfillment of a wild fantasy, but a logical progression for an artistic young man whose personal experiences as a working cowboy gave him a unique opportunity to record the fast-disappearing character of the Old West.

Borein’s maternal grandfather had been one of the most famous horsemen in Alta California, and his father won a lasting reputation for bravery serving under the first sheriff of Alameda County. Born in San Leandro in 1872 and raised in Oakland, young Borein’s earliest interests were horses and cattle and drawing pictures of them. After a few undistinguished years in Oakland’s schools, he began working as a cowboy on ranches throughout California, including a stint at Rancho Jes°s Mar-a at what is now Vandenberg Air Force Base. Fascinated by what he was experiencing, Borein began recording scenes of ranch life. At the urging of friends, he sent some of his drawings to Charles Lummis, the editor of Land of Sunshine magazine, who purchased and published them.tIn 1897 at the age of 25, Borein began the first of many trips to Mexico, where he worked as a vaquero while continuing to sketch his surroundings. Between trips he would return to the Bay Area, contributing illustrations of Californian and Mexican cowboy life to newspapers and magazines, until in 1907 he headed to New York City.

Borein’s studio in the middle of Manhattan, filled with Western and Mexican artifacts, soon became a center for artists, poets, writers, cowboys, and other notables. It was not unusual to find his artist friends Charles Marion Russell, Carl Oscar Borg, Maynard Dixon, and James Swinnerton gathered in his studio, telling their famous stories, eating frijoles, and reminiscing about the West. A number of influential figures in the entertainment world also became members of Borein’s expanding circle of acquaintances, including Leo Carrillo, Will Rogers, “Buffalo Bill” Cody, and Annie Oakley. Then-president Theodore Roosevelt, who was introduced to Borein by the famous actor Fred Stone, became a close friend, and Borein was a frequent visitor at Sagamore Hill, Roosevelt’s home in Long Island.

In spite of his yearning for the West, Borein would remain in New York off and on until 1919. His career progressed steadily during this period, when he worked mainly in India ink and oil paint. In 1914, he began studying etching at the Art Students League of New York, even though graphics was not yet a formal course offering. Shortly thereafter, he had the first of several financially successful solo exhibitions of his etchings, and was elected to the Brooklyn Society of Etchers, establishing him as a bona fide Western artist.

Thanks to a recommendation from his friend Charles Marion Russell, Borein received assignments to do advertising materials for the Calgary Stampede rodeo and exhibition. Borein attended many of the early stampedes, where he sketched most of his bucking horses, including “Swappin’ Ends,” one of a number of bucking horses in this exhibition.

Borein’s friendship with the slightly older Russell was one of mutual professional admiration. Borein held Russell’s work in the highest esteem, so much so that he eventually gave up painting in oils because he felt he could never be as good as Russell. Although Borein’s approach to his artwork later in his career was much more straightforward than that of his friend, Russell’s influence appears frequently in Borein’s early oils and watercolors, as is especially apparent in the paintings of Native Americans included in this exhibition.

In 1919, Borein decided to return to California, where he set up a new studio in Oakland. Decorated with Western and Native American artifacts, Borein’s quarters once again became a gathering place for his many friends. One day in 1921, Borein, now 48 years old, met a striking widow who came to his neighbor’s dance studio for lessons. Her name was Lucile Maxwell, and he married her after a brief, two-day courtship. Following their honeymoon in Arizona, Borein and his bride moved to Santa Barbara, where they would spend the rest of their lives.

When the Boreins arrived in Santa Barbara, the city was already home to a thriving artistic community with many established artists. He adapted quickly, and soon became a well-known fixture in the city. As had been true in New York and Oakland, his El Paseo studio became a gathering place for his many friends, and well-known personalities including the Russells, Leo Carrillo, Walt Disney, Will Rogers, Carl Oscar Borg, and Frank Tenney Johnson were frequent visitors. Borein became very active in the community; he helped organize the first Fiesta Parade and the elite riding group Los Rancheros Visitadores, and was a regular participant in these and other local events.

During this period, Borein perfected the technique of watercolor, which he had first begun experimenting with in Mexico. While his earliest watercolors were simple and crude, his later works in this medium, including two of the Santa Barbara Mission, are far more refined.

Still, etchings remained Borein’s specialty. He loved the medium, creating more than 400 images of cowboys and vaqueros, ranch life, Native Americans and their pueblos, California missions, the Southwest, and stagecoaches. Borein also taught an etching class at the Santa Barbara School of the Arts. Gump’s Gallery of San Francisco held a highly acclaimed one-man show of his etchings, and soon after he was elected to the Society of American Etchers. Borein also illustrated a number of books during the 1920s, among them The Pinto Horse and The Phantom Bull, both by Charles Elliott Perkins. He did two versions of the cover illustration for The Pinto Horse; the alternate version is included in the current exhibition.

Though he died more than 60 years ago, Borein’s reputation as an important Western artist has continued to grow: In 1971, he was posthumously elected into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame, the first native Californian to be so honored. Present-day collectors of Western art also value Borein’s accomplishments. “Borein was the chronicler of the Old West, and he had the artistic ability to translate it into his paintings,” said Van Kirke Nelson of Kalispell, Montana. “He was a master of the etching and watercolor techniques.” Collector Tom Decker of Sun Lakes, Arizona, noted, “The fact that Borein was a participant of the trail-driving era, and a genuine cowboy, resonates with me.” And Ray Harvey of Paradise Valley, Arizona, put it this way: “I enjoy Borein’s work because of his accurate portrayal of the Old West. He painted with more historical accuracy than any artist I know of. Not only did he observe the Old West, he actually lived it. I value that, and I think any serious Western collection must contain an example of his work.”

Academics also recognize the importance of Borein’s contributions. Paul F. Starrs, professor of geography at the University of Nevada in Reno, summarized the thoughts of many in his essay for the current exhibition’s catalog: “Ed Borein came to recognize that he was doing more than producing art. He was also producing a lasting record of times slipping by, and was acting as a pictorial historian, an archivist of the cowboy way.” Through his deep affection for the West and his ability to record with spontaneity the life he knew so well, Edward Borein has preserved in his art a place in time that might otherwise have been forgotten. Thanks to the foresight of his friends and the vision of those entrusted with his work, that legacy will be preserved for years to come.

4•1•1

Coloring the West: Watercolors and Oils by Edward Borein will be on display at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum Gallery (136 E. De la Guerra St.) through February 17, 2008. Admission is free. The museum is open Tuesday through Saturday, 10 a.m.-5 p.m., and Sunday, noon-5 p.m. For more information, call 966-1601 or visit santabarbaramuseum.com.