A Matter of Taste

When Is a Wine Balanced?

It turns out that talking about balance in a wine becomes a subjective undertaking pretty quickly. Some winemakers consider their wines balanced if they prove to taste integrated in their youth; if there is an ample amount of fruit, oak, and spice in a given wine, then it is, in their eyes, balanced. Other winemakers consider a wine to be balanced if it adheres to certain principles, such as if it is varietally correct. Does it possess a reasonable, but not high, amount of alcohol? If it is intended to be dry, is it, indeed, bone dry, free of any residual sugar? And, finally, will it age?

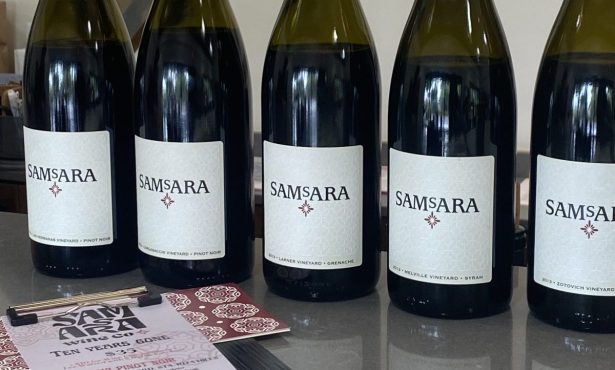

While some purists consider balanced wines to be the best wines, it all depends upon one’s individual expectations of a wine. For example, if you find you love fruit-forward, highly concentrated, extracted wines that are dense, you probably drink many of your wines while they’re fairly young. And, if you gravitate toward wines that are extremely extracted and very fruity, they may also be higher in alcohol. They were, most likely, picked at very high brix levels, and, following fermentation, still have an alcohol level of 15.5-16 percent. There is nothing wrong with liking these kinds of wines; some of the critics’ favorite California syrahs and pinots follow these criteria and are widely well-received.

If you find, however, that you like wines after they have aged, mellowed, and transformed in the bottle, you will more than likely prefer a wine that has a more “textbook” definition of balance. While over-the-top “fruit bombs” tend not to age gracefully, more traditionally balanced wines reveal their tertiary flavors more evenly and, some would argue, more gracefully and evenly.

Try looking at a wine in this way: Wines offer several levels of flavor and aromatics. The primary flavors are the fruit characteristics inherent in a given type of grape. For example, cabernet sauvignons are often described as offering flavors of cassis or currants-these are characteristics true to that varietal. Secondary flavors occur during fermentation and barrel aging. For instance, if that same cassis-like cabernet sauvignon is aged in a brand-new French oak barrel with a high toast, it will also take on flavors that are best described as vanilla- and mocha-like, i.e., flavors that are associated with barrel aging, particularly new barrel aging. Tertiary flavors are flavors that arise in a wine once it has been aged two to five years, or more, from the vintage date on the bottle. These are flavors that occur in the bottle itself, as the wine transforms its structure. In older cabernets that have aged well, one can often detect notes of sandalwood, tobacco, or leather. These more mysterious tertiary flavors are obtained when wines are allowed to age a bit.

The winemaking process really comes into play regarding balance. For example, if a dry wine was bottled with a degree of residual sugar left in it (due to stuck fermentation, or a stylistic decision on the part of the winemaker); if it was picked at very high brix levels to show off youthful fruit; or if it was made in such a way that the fruit was greatly extracted, the result will be a wine that is likely delicious, but may not age well. The high notes of fruit and the possibility of some residual sugar have thrown the wine somewhat out of balance so that when it ages, and the fruit naturally subsides, there may not be enough natural acid and other necessary components to result in a gracefully aged wine.

On the other hand, if a wine was made in a more balanced fashion from the beginning, it will age more evenly. The fruit may subside, but a healthy acid note will still be prevalent so the wine remains lively and can support other flavor components as they arise in the bottle.

It would be short-sighted to say one type of wine is good while another is bad, because it comes down to whether or not you intend to age a given wine, and to what kind of wine you like to drink. Some people find higher-alcohol wines fatiguing while others find them fun and interesting to drink.

This much is true, however: If you’re looking for a wine that will cellar for several years, you’ll want to identify a wine that has been made with an eye toward the traditional definition of balance. If, however, you want to buy a wine that you can drink with dinner that night, you need not concern yourself with great balance.

Of course, some would argue that a balanced wine, even in its youth, offers a more pleasant drinking experience-the tannic structure is more graceful, the flavors are more integrated, the mouth feel is more even, the finish is longer and warm. Others argue that balanced wines, when young, are still somewhat closed and tight. That fruit-forward wines are more fun to drink than austere, balanced wines. Ultimately, balance is in the eye of the beholder.