Working My Way Through a Sleep Disorder

Did Someone Call Me Snorer?

It all started with my wife’s complaints. “It’s not just that you snore,” said she who, truth be told, has made a few angelic buzz-saw sound effects ’round midnight herself. “But sometimes I swear you stop breathing, and it’s scary,” she would add helpfully in front of both friends and strangers. I’d usually make gruff, embarrassed dismissals. “Yeah? You should talk,” was my wittiest riposte.

But the clincher was The Simpsons. Working at home, I’ve carefully apportioned my days to backbreaking work schedules observing strict television avoidance. My early-evening indulgence then was one or two episodes of the Bard of Springfield’s continuing saga. Problem was, I began to doze off five minutes in-and my son began to unkindly compare me with his grandfather, whose rapid entree to 40 winks during bowl games is etched in family legend. Worse, I began to indulge in after-lunch naps, but even so fell to rattling dozes during sitcoms, boring lectures, slow films, and many a night of theater.

So I dutifully informed my doctor during an annual check-up. Given the symptoms and the buzz I was hearing from my now also decrepitating friends, I suspected I might have sleep apnea. The doctor was concerned with an edge of skepticism. Though he willingly referred me to a sleep specialist, he tutted somewhat grumpily, “You could probably stop snoring :” he said in a hesitant voice that trailed off suggestively. “If I lost weight,” I said, finishing his sentence. He nodded and then suggested a number of pounds that left me gasping for air.

It was true and I knew it, but I was reluctant to give over another indulgence to the dubious principle of acting my age. I’d quit drinking and all other ancillary intoxicants some years earlier. I hadn’t smoked since Clinton was first elected. But dieting? It seemed so unnatural somehow, especially for a person who wrote about food. Perhaps a sleep specialist could prevent apnea without sacrificing my few remaining vices.

Two weeks later I was face-to-face with a man obsessed with sleep. Andrew Duncan is a physician’s assistant with a Scottish brogue and near irresistible brio, and he met my worries with a rush of words. “Half of this town is sleep-deprived,” he said, adding that our emergency people like police, firefighters, nurses, and doctors are perhaps worst of all. When I mentioned my doctor’s weight-loss theory, Duncan laughed. “With all due respect,” he said, “he has it exactly wrong. If you get over the sleep disorder, the pounds will roll off you.” Now I was intrigued.

The sleep checkup included vital sign monitoring and a peer into my throat, which unleashed concerned mutterings to the effect that my cruel DNA had left me overstocked with superfluous tissue or redundant tongue-al matter, or something technical that translated into an insufficiently open throat, which would ineluctably shut tighter as I entered dreamland. Not good, was the diagnosis. It was reinforced, oddly, by a multiple-choice test I took, the most poignant question being a query as to whether I felt an overwhelming urge to sleep when my car reached a stop sign. They are inside my head, I thought. Duncan said the sleep-deprived mind sought every opportunity to catch up, even in unsafe situations. He deemed me an excellent candidate for a sleep study: I was to bring my pajamas back to the office later next month for a sleepover. I had to go buy pajamas.

The scheduled night, I arrived having dutifully obeyed restrictions against napping during the day or imbibing caffeinated bevs. Upon arrival, a nice young woman gave me a brief precis of the evening’s proceedings, showed me my quarters-like a nice hotel room hung with medical electronica-and then let me watch television, and prepare mentally to drowse. I was to contact her via intercom when ready for bed. Actually, I was wired first, which turned out to be a medium-encumbering set of electrodes from chest to scalp. As I hefted my corporeal self onto the comfy bed I felt mildly ridiculous but surprisingly ready to sleep. She ran me through a few tests: Hold your breath, wiggle your toes, etcetera. I felt a bit self-conscious rolling into dreamland wired and recorded. Suffice it to say, I lay there, lights out, wires attached, for what seemed an inordinate period. Next week, when my data was shared, it showed that it took me a whopping eight minutes to grapple into the arms of Morpheus.

I was warned, however, that if my sleep architecture (charming poetic term) became bad, I would be awakened by my attendant and an air-supply mask would be attached. This indeed happened somewhere around

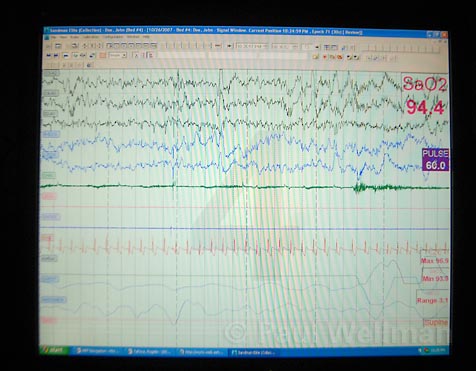

2 a.m. Despite the bizarre interruption, I slept beautifully until they woke me at 6 in the morning. And I have the spreadsheet to prove it. Machines mapped my entrance into the levels of sleep including REM (rapid eye movement restorative) slumbers. My awful snoring didn’t really prevent me reaching proper levels, though, shockingly, I sometimes stopped breathing for more than a minute. My oxygenation was horrifyingly low at times and my heartbeat and respiration was wacky erratic. At my follow-up appointment I learned I was an excellent candidate for the very machine applied that fate-determining night, which would blow air into my throat all night long for the rest of my life-which would be, ironically, I guess, extended by a REMStar M Series, which I was instructed to employ at its utmost setting.

Let’s just say that I moped in the days between prescription and fulfillment. In lighter moments I feared becoming Darth Vader. Taken soberly, I saw it as the first of a long series of humiliating medical interventions. The thin edge of mortality’s wedge.

Only sometimes do I wear the pajamas I bought, but I do use the whispery quiet machine nightly-for more than a year now. I even associate the way it puffs air through the mask with the more pleasant aspects of hibernation-weirdly Pavlovian, that. I like sleeping.

I like breathing, too.

I didn’t lose weight as effortlessly as Andrew Duncan promised. (Though I subsequently went on a diet and lost all that my doctor suggested.) I sleep through the night; I’m rested, though not exactly an ebullient adolescent again.

However, I did stop sleeping during movies and lectures, and I don’t feel like napping at stop signs, which is a good thing for all of us. Besides, staying awake during The Simpsons surely helps develop that ultimate immunity to life’s harsher edges-a better sense of humor. And then, who knows, I might even be able to admit my wife is right next time she saves my life with her incessantly kind complaining.